On July 13, football fans around the world watched the World Cup final between Germany and Argentina, held at the Brazil’s most famous Estádio do Maracanã in Rio de Janeiro. Despite the national team’s disappointing performance, overall this was a very successful event for the national and local governments, in a relatively peaceful environment.

The government’s pacification strategy, which consists of military-style operations conducted by Rio’s notorious Special Forces followed by a permanent police presence of UPPs (Police Pacification Units), has been at the forefront of drastically reducing violence and crime in the city. Yet this may not provide a complete picture of events. In the months leading up to the World Cup, there was a noticeable upsurge in violence, pointing to the fragility of the overall security stabilization process and the underlying challenges that the city faces in the coming years.

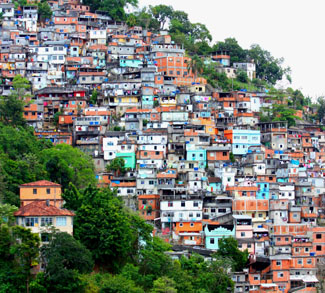

Although police operations have been able to largely neutralize gangs in targeted areas, they have had the effect of displacing the criminal activity elsewhere. Evidence shows that drug bosses are increasingly taking their business to the outer city districts such as Baixada Fluminense, where police presence is still minimal. At the moment, UPPs are still operating in only a few districts, particularly in areas close to focus neighborhoods such as Jacarepaguá or Cidade do Deus, or those that are undergoing rapid gentrification; there are still large swathes of Rio’s slums under the control of gangs. Although the government has plans to expand its range of operations, there is no indication that it will be doing so in the near future. On the other hand, there are signs that the security situation has been slowly deteriorating in previously pacified areas. UPPs have become targets of returning drug traffickers that are intent on recovering their territory.

This all points to the difficulty the government faces in maintaining control without falling back on a heavy police presence, as well as the limited resources available to Rio’s police force in tackling the gangs that operate across the city’s expansive slums.

Adding to these operational and resource challenges is the issue of police corruption, which recent reports indicate is endemic in Rio. Residents are not only routinely extorted for money but in many cases corrupt police divisions collude with local criminal gangs in drug and weapon trafficking. Although the BOPE Special Forces has so far escaped this problem – due in large part to a rigorous selection and oversight program – the same cannot be said for the less trained and more plentiful UPP forces. The continuous inflow of money and weapons to the slums, partly due to rogue elements in the police, has reinforced existing criminal networks, threatening to stall and perhaps reverse the improvements seen until now. Over the years, there has been a concerted effort to stamp out corruption; however, the relatively low wages given to regular police units provide them with a strong incentive to engage in more lucrative criminal activities. Added to this is the prevalence of patronage and misconduct at the force’s higher levels, which thwart efforts to increase transparency and accountability.

There is also the chronic problem of police brutality, which has fueled public distrust and friction in a number of favelas. The most recent example occurred in Complexo da Maré, a slum with a long history of anti-police sentiment. Incidents like these, which are still commonplace in both new and retaken slums, have hindered the already strained relations between police and local residents. In previous years, the authorities’ strong-handed approach has contributed to a reduction in gang activity, but it is coming at a rising cost where it could fast become counter-productive. There has also been increased militarization recently in a number of slums, which itself may be very problematic, as it is contributing to a siege mentality among local residents – exacerbated by the fact that many of these units do not have proper policing skills. Heavy-handed policing risks squandering the gains already made by the UPPs and social investment programs under the government’s pacification strategy.

Although it should be noted that the police continuously tries to tackle some of these problems, it is unlikely that there will be any meaningful change until the situation becomes unmanageable.

Rio’s crime and violence is derived from a layered and complex socioeconomic context that requires a long-term strategy and political commitment; nevertheless, as long as the government does not tackle the endemic problems within its police force, it is unlikely that it will be able to create the proper conditions for a lasting peace and security.