Summary

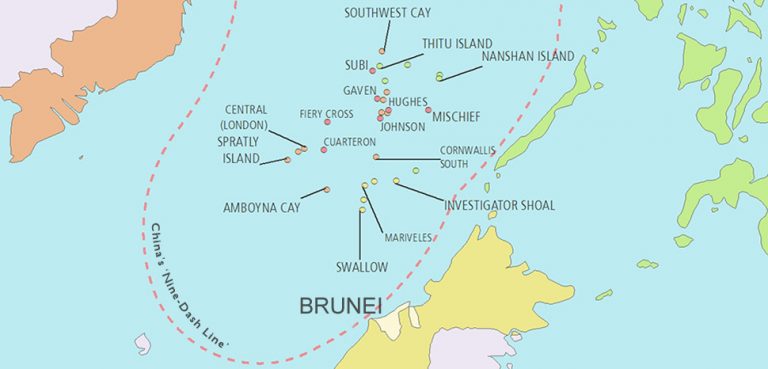

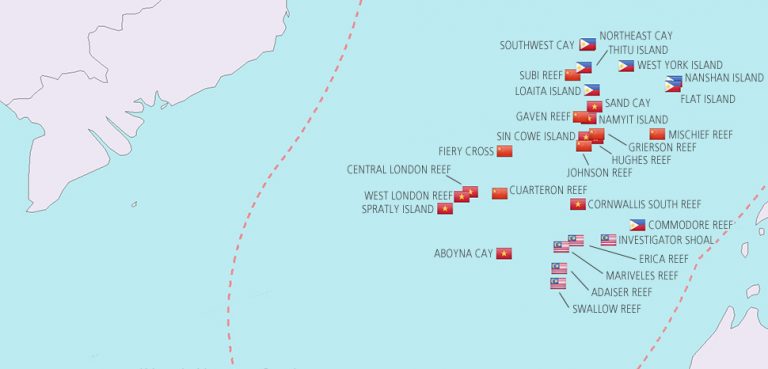

The Eastern Mediterranean has seen the birth of some of history’s greatest civilizations, and the most disparate cultures have met along its shores through trade and war. Today, this tradition continues in the form of a continuously shifting mix of cooperation and competition among the states located in the area. As a matter of fact, this maritime region witnesses a complex and dynamic interplay of interests among its main players, each one of which has a distinctive socio-political nature and specific objectives. The recent discovery of lucrative gas and oil deposits below its waters has the potential to reshape the regional geostrategic framework and open a new phase in the relations between the states along its shores, notably one marked by increased competition and maritime skirmishes. It’s a dynamic that shares a lot of similarities with the South China Sea dispute in Asia.

Background

A prominent feature that has marked the geopolitical asset of the Eastern Mediterranean since the rise of civilization has been its position as a crossroad between three continents: Europe, Asia, and Africa. Today’s regional power distribution reflects this centuries-long status. States like Greece, Turkey, Israel, and Egypt all play a major role in this area; but Iran and the EU (through Greece and Cyprus but also Italy and France, whose energy firms are present in the region) have also considerable stakes there. Moreover, great powers like the U.S., Russia and now even China (with the OBOR initiative) are involved as well.

This intricate network of diverging interests and opposed identities, combined with the area’s intrinsic geostrategic importance, explains why the Eastern Mediterranean is characterized by so many conflicts and territorial disputes. In this context, the recent discovery of important hydrocarbon deposits has the potential to make the situation even more tense. Drilling exploration activities have increased in recent years, and a number of promising offshore gas fields have been discovered, thus attracting the attention of major energy firms like Exxon Mobil, Total, and ENI. A 2010 study estimated that the area hosts 122 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 1.7 billion barrel of oil reserves, with some sources reporting even higher figures. But in such a crowded region, determining who has the right to access and exploit these resources can be problematic, as it requires reaching an agreement on the respective Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). While sometimes this has been done with success (like in the Israel-Cyprus and Egypt-Cyprus cases), other times the demarcation remains disputed. That said, some rich deposits are located far from the coasts of Israel and Lebanon (like the Tamar and Leviathan field); some close to Egypt (notably the Zohr field, the biggest one in the region); and others in Cyprus’ EEZ, like the Aphrodite and Calypso fields. The latter is the most recent discovery in the Eastern Mediterranean, and it has already sparked clashes in the region. Among the conflicts and disputes characterizing the area, three assume a greater importance in the light of recent gas discoveries: the Israel-Lebanon maritime border dispute, the war in Syria, and finally the Cyprus question.

Impact

Israel and Lebanon have not reached an agreement on the delimitation of their respective EEZs, and since some interesting gas deposits lie next to the coast of both states, there is no agreement over who owns these resources. Of the two, Israel clearly has the upper hand, and has adopted a firm stance to assert its right to exploit the area’s hydrocarbons. But things are not so easy, as Beirut has protested these moves with Tehran’s support. Most importantly, the Lebanon-based Hezbollah, the powerful Shiite militia backed by Iran, has threatened to hit Israel’s ships and facilities involved in offshore hydrocarbon exploitation if Israel interferes with Beirut’s gas development projects. As such, and considering all the other sources of tension, the situation could rapidly escalate. In particular, Israel may decide to launch a new offensive in southern Lebanon to tackle the Hezbollah menace and affirm manu militari its maritime claims, and in turn its access to the sea-based fossil fuels, thus opening another “hot” front in the war that is currently devastating the Middle East.

This is not a case of Iran supporting Lebanon strictly for the latter’s sake. Tehran has specific plans with regards to the Levant and Eastern Mediterranean, which also explains its stance in Syria. This country has been torn by a devastating war since 2011. While it was not a significant hydrocarbon producer and it remains unclear how much untapped reserves it has, Syria still has a notable importance in the energy geopolitics of the Eastern Mediterranean as a pipeline crossroad. In the wake of the Syrian civil war and the Western-backed sanctions, Damascus can no longer export its fuel to Europe as it was doing before the war. A solution is to diversify its exports by cooperating with Iran and Russia. The former planned to build a pipeline to the Mediterranean and Europe through northern Iraq and Syria, something that explains Tehran’s presence in these two states and its firm support to the Assad regime. For its part, Moscow sees Syria as an important conduit of access to the Mediterranean Sea, also in energy terms. It should be noted that last January Russia obtained the exclusive right to produce oil and gas in the country. Again, this helps to better understand why the Kremlin has been sustaining Assad’s government: its victory in the civil war would allow Russia not only to strengthen its position in the Middle East, but also (if it accepts to shoulder the considerable costs of rebuilding Syria’s energy infrastructure, estimated at 35-40 billion USD) to access the Eastern Mediterranean’s fossil fuel deposits. What is important is that the Russo-Iranian projects in the region would bypass Turkey, reducing the political leverage it enjoys as an essential pipeline crossroads between East and West. In this light, Ankara’s intervention in Syria is not simply an effort to stop the formation of a Kurdish state, but also a measure to avoid the realization of such pipeline projects that would reduce its geoeconomic relevance.

It is therefore clear that the Syrian war is also about accessing the Mediterranean and its fuel deposits, and this brings us to the final conflict zone: Cyprus. Apart from being relevant on its own, the island is also closely related to the other conflict areas described above, and it has even been speculated that the Syrian conflict could spill over into Cyprus. The discoveries of the Aphrodite and Calypso fields have raised hopes of making the island into the hub of Eastern Mediterranean energy producers, and even providing an opportunity to solve the longstanding dispute between the Greek south and the Turkish north, divided since 1974. But in regard to the second item, the result appears exactly the opposite. The prospect of an energy richness only fomented the dispute over who should access the resources and how they should be distributed. In this context, Ankara has adopted an aggressive stance, and has not hesitated to employ the military to protect its interests. The most notable episode occurred on February 9, when Ankara’s navy prevented the Saipem 12000, a drilling ship owned by Italy’s ENI, from conducting gas exploration activities off the Cypriot coast, thus leading to a bitter exchange of accusations between all parties involved. In particular, the Turks have accused the Greek-Cypriot government of unilateral actions to exploit the energy deposits to the exclusive benefit of the Greek community, while Nicosia expressed concern over Ankara’s threat to use force. And there is more. Turkey has also conducted provocative actions in the Aegean, probably to dissuade Greece (a close partner of Cyprus) from intervening over the issue. On February 12, a Turkish patrol boat rammed a Greek one close to the disputed Imia / Kardak islands. Another incident occurred on March 1, when two Greek soldiers were captured by a Turkish patrol after crossing an unclear section of the border between the two countries, causing tensions to rise again. But Turkey’s assertiveness in reaffirming its claims also involves other countries, notably Egypt. Apart from the discontent with Ankara’s support for the previous Muslim Brotherhood government, current Egyptian President el-Sisi is also pursuing important projects to develop the country’s offshore gas reserves, also in cooperation with Cyprus and Israel. In this regard, Egypt has recently signed a 15-billion USD agreement for importing gas from the latter. But Egypt’s plans clash with Turkey’s, and this is problematic considering that Cairo has equally expressed a firm willingness to defend its right to exploit the Eastern Mediterranean’s energy resources.

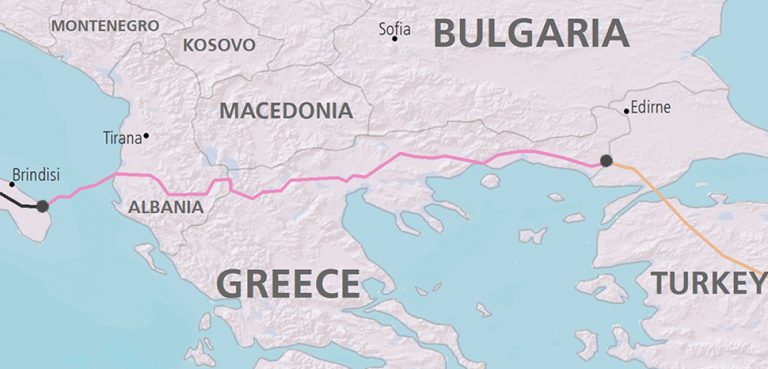

As such, Ankara’s behavior resembles that of Beijing in the South China Sea. And similar to what happens there, it is alienating the other players in the area, thus pushing them into closer cooperation to the point that an anti-Turkish alignment is gradually emerging among Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt. The first three of them are reinforcing their energy and defense partnership, and along with Italy have reached an agreement to build a new pipeline to Europe. For its part, Egypt hopes to become part of the deal by connecting its Zohr field with this pipeline. But like the Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline, similar projects bypass Turkey, which explains its staunch opposition. Ankara’s actions to assert its claims over the Eastern Mediterranean are therefore as much a way to access its hydrocarbon deposits as well as an effort to stop the construction of pipelines that would circumvent its territory and therefore reduce its economic, political and strategic leverage.

Forecast

This overview shows that Cyprus is at the center of the gas geopolitics in the region, and that Turkey is acting aggressively to ensure its access to such hydrocarbon deposits and avoid losing its status as a key energy crossroad. Important gas fields are located close to Cyprus, and the existing disputes are largely based on how Nicosia has delimited its EEZ with neighboring countries. But Ankara, leveraging on its influence over the northern part of the island, denounces such agreements and does not recognize them, and goes even further by exploiting its influence over Turkish Cyprus to advance its claims.

Yet this in turn causes other powers to react by enhancing their cooperation following an anti-Turkish logic. If Ankara continues to take assertive actions, it is likely this trend will be reinforced and that the risk of conflict will rise in the Eastern Mediterranean, notably over Cyprus and its waters. If tensions were to rise to a crisis level, the Turks may even launch military operations on the island. Similar scenarios would be very serious, as they would involve powerful states in a densely-populated area of central importance for international trade, as the flow of goods from Asia through the Suez Canal passes right through it (without forgetting the Bosphorus-Dardanelles).

But what is more likely to materialize, at least in the short term, is the emergence of hybrid warfare actions based on the empowering of coast guards and the formation of naval militias akin to what happens in the South China Sea. As a matter of fact, the similarities between the two maritime regions are stunning: in both cases there is a vast sea zone of primary importance for international trade and believed to be rich in resources upon which a major state (China in the SCS, Turkey in the Mediterranean) advances its claims by adopting an assertive diplomatic-military stance, thus causing neighboring powers to react by strengthening their mutual cooperation. Akin to what China does in the SCS, it is possible that Turkey will develop its maritime law enforcement units, create naval militias, set up logistic/military facilities (notably in Northern Cyprus, where it already stations military units) and conduct intimidating maneuvers to assert its influence over the area, to harvest its resources, and to avoid being bypassed by the construction of new pipelines. Again, similarly to what happens in the SCS, this increases the risk that an incident may escalate to a broader armed conflict with devastating and unintended effects. And considering the growing energy demands in the area and beyond, this is not an unrealistic scenario over the long term.