The South China Sea remains at the epicenter of one of the most volatile maritime areas in the world, with little or no agreement on sovereignty claims to the ownership of atolls, submerged banks, islands, reefs and rocks. Yet South China Sea fishermen, marine biologists, and policy shapers agree that without an end to unsustainable fishing practices and urgent adoption of environmental protection measures, a catastrophic marine biodiversity and fishery collapse is imminent.

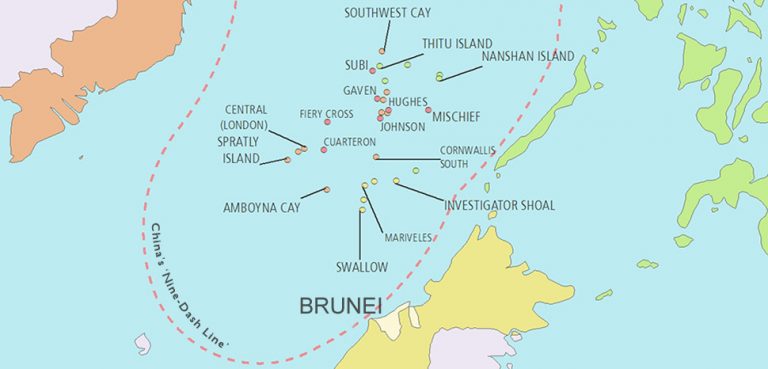

Beijing’s accelerated land reclamation over these specks of rock in the roiling sea is increasing friction among other claimants like Vietnam and the Philippines. Moreover, the Chinese-directed Spratly Island building expansion on the Johnson, Cuarteron, and Gaven reefs wrecks rich fishing grounds and valuable coral reefs in the archipelago.

The daily dumping of landfill with sand dug from nearby reefs by Chinese laborers, “upsets the marine ecology of the region, completely destroying the formed coral reefs that are hundreds of millions years old. At the same time these actions destroy the habitat of many marine species. Protecting the marine ecological environment is a global issue and citizens all over the world are responsible for that,” claims Dr. Le Van Cuong, former director of the Institute for Strategy and Science and a recognized expert on the South China Sea.

Flashpoints continue in the Scarborough Shoals with critical potential at the Paracel Islands, (China occupied, Vietnam claimed). At this desolate rock formation of the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ), Chinese vessels violently ram Filipino fishermen boats and illegally remove endangered giant clams.

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) senior fellow Gregory Poling believes “anxiety and the expanded patrol and surveillance capacity that Beijing is constructing with facilities, docks, and probably at least one airstrip in the Spratly Islands will complicate the disputes in the South China Sea.” Satellite images confirm the Middle Kingdom’s illegitimate territorial expansions, raising fresh concerns from the United States and Asia.

Last year, the international media was drawn to the standoff between China’s $1 billion forty-story oil rig parked approximately 120 miles from Vietnam’s coast, near islands claimed by both countries. This test of geopolitical limits resulted in China removing its rig but not its resolve.

China Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s claims, “we are in this boat together with more than 190 other countries. So of course we don’t want to upset the boat, rather we want to work with other passengers to make sure this boat will sail forward steadily and in the right direction.” This diplomatic metaphor does nothing to diminish the Middle Kingdom’s worsening coastal fishing crisis that propels their streamlined steel trawlers into deeper contested waters. In response, Vietnam’s fishermen have been granted generous soft loans to replace their traditional wooden boats with steel hulls. Hanoi recently trumpeted that the country will have 30,000 new trawlers plying the East Sea and beyond by 2020.

Policy shapers and researchers believe whether or not there is a repeat appearance of the oil rig HD 981 or redeployment of the Hainan Baosha 001, a 32,000 ton fish factory vessel with its four processing plants and 600 workers, it “ raises legitimate questions about the basis of China’s claim to fish in the East Sea,” claims, Youna Lyons, a senior research fellow at National University of Singapore. After all, exhaustion of fish stocks belonging to Vietnam and the Philippines are a direct violation of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Marine science and geopolitics are converging more than ever in the South China Sea.

The food security and renewable fish resource challenges are clear. According to a World Bank Fisheries Outlook, “Fish to 2030: Prospects for Fisheries and Aquaculture,” China will increasingly influence the global fish markets. A baseline model projects that China will account for 38 percent of global fish consumption by 2030.3The United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) confirms that the South China Sea accounts for as much as one tenth of global fish catches. A clear trend is emerging: overfishing and widespread destruction of coral reefs.

Marine scientists express concern for the plight of the region’s hard and soft corals, parrot fish, spinner dolphins, sea turtles, groupers, and black-tipped reef sharks. From Vietnam’s coastal areas to Hainan Island, the region has a 60 percent coral life and 50 percent fish species decline respectively. El Nino (2008) caused short-term increases in water temperature, resulting in widespread coral bleaching and death of precious coral formations.

A perfect storm is swiftly blowing across the region, like a fast moving typhoon. The litany of intractable issues mount daily: global warming, destruction of reefs, overfishing, destructive fishing practices, advancing technology, an increase in the number of state-of–the-art fishing boats, unregulated fisheries, and population growth.

Bill Hayton’s The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia asserts that overfishing remains one of the major issues that must be addressed in the region since China encourages its fishermen to trawl through contested waters. “During the 2012 (fishing) ban, the Hainan Province Department of Ocean and Fisheries organized the largest-ever Chinese fishing fleet to reach the (Spratly) islands: 30 vessels including a 3,000 ton supply ship.”

Since 1985, China, Vietnam, and the Philippines have included large-scale explosive and cyanide fishing operations in the Spratlys. Marine biologists estimate that fishing will need to drop by 50 percent to sustain target species.

Where are the regulatory bodies to sanction all trawlers, purse seines, gill nets, drift nets, castnets, beach seines, surface long lines, bottom long lines, trolling lines, hook and lines, fish pots and destructive fishing practices like using cyanide and dynamite?

Advocates for Marine Peace Parks, (MPAs) vital sanctuaries safe from oil and gas exploration, mining, and assorted commercial fishing nets, agree there is a history of South China Sea marine science cooperation.

“In some cases, it might be easier to set-up informal international activities by sponsoring participation in scientific and conservation research by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that can affect protection with seasonal and zonal restrictions,” claims John McManus, biologist and director of the National Center for Coral Reef Research (NCORE).

There are recent historical markers for such cooperative scientific research efforts. For example, the intergovernmental, multinational Coral Triangle Initiative (2009) encompasses Indonesia, the Philippines, Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. In this area hosting more than 600 species of coral, 3,000 fish species, and the world’s largest mangroves, this initiative enables regular marine science dialogue and effective political cooperation despite its non-legal character.

Last year’s Global Oceans Action Summit for Food Security and Blue Growth, held in The Hague, brought together global leaders, ocean practitioners, scientists, NGOs, and international agencies like the World Bank, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and others. They acknowledged that 3 billion people currently depend on fish for twenty percent of their average per capita intake of animal protein. Also, between 660-820 million livelihoods or almost 12 percent of the world’s population are dependent on fisheries.

The challenges are hard to ignore: how to feed over 9 billion people by 2050, in the face of climate change, increased competition for marine resources, overfishing, habitat change and coastal pollution. The problems warrant faster solutions.

Why not call for a South China Sea environmental summit; a collaborative strategy established by a joint South China Sea Marine Blue Commission made up of marine scientists and policy shapers to address trans-boundary issues, to create regional fishery bodies, to promote designated marine reserves, especially in the Spratlys, and to encourage citizens to petition their governments to adopt the necessary marine conservation practices now before it is too late.

Put simply, perhaps this message from John Gruver of the United Catcher Boats Association is what the South China Sea fishermen need to practice: “The fisherman of the future isn’t going to be measured by the fish he does catch, but by the fish he doesn’t catch.”

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.