The increasingly loud accusations and declarations from Beijing and Washington over China’s ambitions to reclaim a string of small islands, coral reefs and lagoons show no signs of ending. However, given the number of international stakeholders in the region, the real promise of science for diplomacy may now be at hand in this complex geopolitical climate.

The arena for this convergence of two words- science and diplomacy- was displayed at a Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Washington symposium, where marine science, and the emergence of China’s ‘blue economy’ framed a new narrative in understanding the environmental stakes in the region’s escalating conflict.

Panelists Dr. John McManus, Rosentiel School of the University of Miami, and Professor Kathleen Walsh, U.S. Naval War College, demonstrated to policymakers how this contested region is not simply about sovereignty claims, but is likely to be recognized as one of the most significant environmental issues of the 21st century.

Policymakers may do well to take a lesson or two from nature as they examine how best to address the complex and myriad of sovereignty claims. Just as scientists place their subjects under close microscopic inspection, the policymaker, now more than ever, needs to visit science laboratories, where many contested nations’ researchers are sharing data about the future of South China Sea coral life.

At the 16th Meeting of the ASEAN Working Group on Coastal and Marine Environment held last month in Singapore, Dr. Leong Chee Chiew, Deputy CEO, National Parks in Singapore highlighted that the ASEAN region, with its combined coastline of about 173,000 kilometers and rich coastal and marine biodiversity, faces enormous challenges to sustainability in coastal and shared ocean regions. Unless a scientific ecosystem approach is adopted, trans-boundary marine areas conflicts will only become worse.

The problems are disturbing. Nearly 80 percent of the SCS’s coral reefs have been degraded and are under serious threat in places from sediment, overfishing, destructive fishing practices, pollution and climate change.

Challenges around food security and renewable fish resources are fast becoming a hardscrabble reality for more than just fishermen. With dwindling fisheries in the region’s coastal areas, fishing state subsidies, overlapping EEZ claims, and mega-commercial fishing trawlers competing in a multi-billion dollar industry, fish are now the backbone in this sea of troubles.

An ecological catastrophe is unfolding in the region’s once fertile fishing grounds, as repeated reclamations destroy reefs, agricultural and industrial run-off poison coastal waters, and overfishing depletes fish stocks.

A recent issue of The Economist underscores the importance for science diplomacy: “The littoral states ought to be working together to manage the sea, but the dispute over sovereignty fosters the fear that any collaboration will be taken as a concession.”

The United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) confirms that the South China Sea accounts for as much as one tenth of global fish catches and by 2030, China will account for 38 percent of global fish consumption. Overfishing and widespread destruction of coral reefs now necessitates the intervention of science policy to safeguard the stewardship of this vital sea.

The immense biodiversity that exists in the South China Sea cannot be ignored. The impact of continuous coastal development, escalating reclamation and increased maritime traffic is now regularly placed in front of an increasing number of marine scientists and policy strategists.

Marine biologists, who share a common language that cuts across political, economic and social differences, recognize that the structure of a coral reef is strewn with the detritus of perpetual conflict and represents one of nature’s cruelest battlefields, pitting species against species. At the same time, the coral reef, often referred to as a jewel of the sea, offers a sanctuary to many of the sea’s life forms like the mollusk, which in turn provides lodging to a mantis shrimp and a miniature eel in exchange for food and cleaning services.

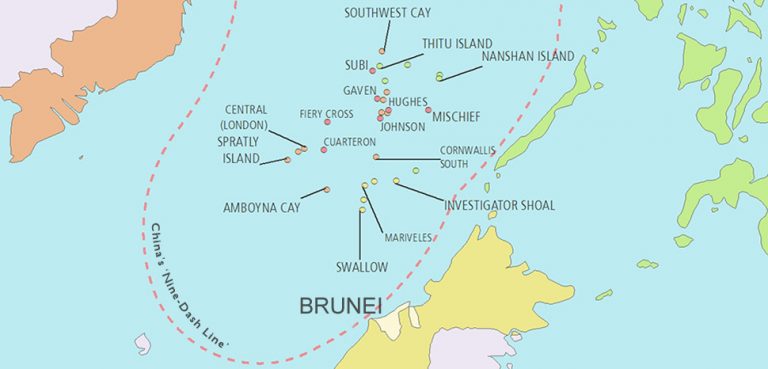

While traditional diplomatic and military tactics are not completely exhausted in the latest round of diplomatic salvos between China and the U.S., perhaps the timing is excellent for the emergence of science as an optimal tool to bring together various claimants, including Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Taiwan in the highly nationalistic contested sea disputes.

For the analysts and ministry policy shapers, this means a shift of focus, away from military capacities and maneuvering of naval vessels and surveillance planes to a deepening of registers and practices found in science diplomacy. If the U.S. and China are to find substantive common ground in this complicated and intractable history, it requires a creative and flexible diplomatic policy. That bridge for communication may be tapped among marine scientists currently engaged in cooperative research in the region.

For example, the build-up of maritime biology, maritime mapping and geology, deep-sea explorations, and systematic knowledge production was absent only 20 years ago. However, these scientific advancements fail to support a Chinese position with the UN Seabed Commission, and in other legal battles in the context of international law of the seas. On the contrary, the Commission fosters and provides the framework for the expansion of cooperative research in scientific marine study on deep-sea ecosystems.

In an amplification of science’s vaulted role, the International Seabed Authority is involved in the vast effort of collecting, analyzing, rationalizing, and disseminating results of marine scientific research and data. Their one hundred and sixty seven members, including China, recently met at the United Nations to develop and to discuss the exploitation code.

The scientific community does not refute the overwhelming evidence that China’s continued reclamation of atolls and rocks through the dredging of sand in the Spratlys disrupts the fragile marine ecosystem. The area has been recognized as a treasure trove of biological resources and is host to parts of Southeast Asia’s most productive coral reef ecosystems.

With coral reefs threatened around the world, reef specialist, Dr. McManus in his CSIS presentation, expressed concern for the plight of the region’s hard and soft corals, parrotfish, spinner dolphins, sea turtles, groupers, and black-tipped reef sharks.

Recent biological surveys in the region and even off Mainland China reveal that the losses of living coral reefs present a grim picture of decline, degradation, and destruction. More specifically, reef fish species in the contested region have declined precipitously to around 261 from 460 species.

While science provides as many answers as questions, the evidence is alarming that the world may be witnessing a reef apocalypse. This crisis should weigh heavily on all claimant nations who need the fish protein to feed a burgeoning 1.9 billion people.

As early as 1992, McManus was one of several marine scientists who wrote scientific articles advocating for an international peace park or marine protected area. While the geopolitical intractable SCS impediments remain, the Spratlys might be seen as a “resource savings bank,” where fish, as trans-boundary residents, spawn in the coral reefs and encircle almost all of the South China Sea waters, before returning home.

In an e-mail, McManus acknowledged that others have added international gravitas in the call for a marine protected area in the Spratlys. They include, Dr. Liana Talaue-McManus, his wife and an expert on resource management, Dr. Porfirio Aliño, a coral reef ecologist, and Dr. Mike Fortes, a seagrass ecologist, and Dr. Alan White, a senior scientist at the Nature Conservancy, now responsible for the Coral Triangle Program, representing a coordinated conservation policy driven effort on the part of six countries including, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, the Philippines, Timor Leste and Malaysia.

Additional marine protected area endorsements have come from conservationist Tony Claparols, former Philippine President Fidel Ramos, Vietnam’s Dr. Vo Si Tuan and Taiwan’s, Dr. Kwan-Tsao-Y Shao.

The Nature Conservancy report ‘Nature’s Investment Bank’ points to improved fish catches outside MPA boundaries, increased protein intake and even poverty alleviation through ecotourism. Because of earlier scientific work and published articles, the Taiwanese government recognized Dongsha atoll’s prominence as a model for the sustainability of fishery resources in the SCS and the Taiwan Strait and was designated as the first marine protected area in March 2004.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) provides a generous definition of trans-boundary conservation: “in its simplest explanation, trans boundary conservation (TBC) implies working across boundaries to achieve conservation objectives,” writes Maja Vasilijevic, chair of the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas. Scholars or scientists should provide the interpretations and guidelines for the establishment of trans-boundary-protected areas.

The classic example of ‘science diplomacy’ was the original Antarctic Treaty, which most consider to have been a direct and natural extension of the multinational research in Antarctica associated with the International Geophysical Year studies in 1957-1958. Marine scientists have disclosed that a similar well-funded project in the South China Sea would be the natural lead-in to a Spratly Island agreement. There have been several international projects in the region. However, the ones that had a serious emphasis on the Spratly Islands have been minor because of the regional tensions.

The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) is a committee of the International Council for Science (ICSU) charged with the initiation, promotion, and co-ordination of scientific research in Antarctica. SCAR is an international, interdisciplinary, non-governmental organization that can draw on the experience and expertise of international scientists. Another function of SCAR is to provide expert scientific advice to the Antarctic Treaty System.

Science Councils and Treaties Offer Diplomatic Solutions

Antarctica is the one place that arguably is the archetype for what can be accomplished by science diplomacy. Under the Antarctic Treaty, no country actually owns all or part of Antarctica, and no country can exploit the resources of the continent while the Treaty is in effect.

Over time, the Antarctic Treaty has developed into the Antarctic Treaty System, which includes the protection of seals and marine organisms and offers guidelines for the gathering of minerals and other resources.

Additionally, the Arctic Council has been able to effectively steer the passage of domestic legislation, international regulations, and, most importantly, international cooperation among the Arctic States. Eight nations—Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States—have territories (claims) in the Artic, and the domestic laws of these nations govern actions taken within their territorial waters.

Many of the adopted Arctic Council key recommendations could be adopted for the South China Sea: create a South China Sea Maritime Council or SCS Oceanographic Council; the United States should ratify UNCLOS to enhance U.S. authority on SCS issues; develop improved communications, standardized procedures and multilateral training for search and rescue, military movements, natural disasters, maritime awareness, oil spill management, shipping infrastructure, and oil, gas and mineral development; identify priorities for scientific study; develop more small-scale and renewable energy projects to improve the economic future of small communities; improve individual and community health and food security; and improve early-warning systems for environmental change.

Unfortunately, none of these recommendations are operative in the political currents of the South China Sea. Dr. Michael P. Crosby, President and CEO of Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida weighs in on benefits of using this paradigm for interactions between scientists and resource managers through international marine science partnerships. He has even extolled the merits of the Red Sea Marine Peace Cooperative Research, Monitoring, and Resource Management Program (RSMPP). Crosby states that “RSMPP may serve as a model for improving international relations and building capacity through marine science cooperation.”

Asia has the world’s largest fishing fleets, representing nearly three million of the world’s four million fishing vessels. And most estimates show that the numbers are increasing. China’s fleet of 70,000 fishing boats, the largest in the world, is increasingly flaunting the few international rules that exist around fishing. With other coastal claimants like the Philippines and Vietnam increasing their fishing fleets, it’s not surprising that China is rolling out a “blue economy” plan.

Professor Kathleen Walsh’s scholarship on China’s rising blue economy reveals that some Middle Kingdom marine scientists are concerned about conservation and sustainability issues. After all, coral reefs once found off China’s own shores have shrunk by an astonishing 80 percent over the last 20 years. Pollution, overfishing and coastal development are blamed for this environmental collapse. In her examination of China’s blue economy, which includes marine, maritime, and naval sector ambitions, Walsh argues that China’s new maritime development programs could have a big impact on the United States and other nations. According to her (disclaimer: these are her personal views and not the U.S. Department of Defense, US Navy or US Naval War College), Chinese leaders are looking at water resources—including coastal areas, rivers, lakes, and oceans—as the nation’s next economic development frontier.

Perhaps at the first sight, these observations and practices seem unconnected. But they operate together, and this notion of a Blue Economy reflects all of the elements of a broader strategic planning in Beijing.

But the crucial point here is that the assemblage of the South China Sea is increasingly shaped in scientific terms. Nevertheless, it’s painfully clear that today’s ecological policy issues face formidable challenges to inform policy deliberations. In other words, as the disposition of regional maritime space becomes greater, adding seabed research, geology and mapping, deep-sea biology, underwater archeology, cultural registers, environmental symposia, marine protected areas and art history, there are more avenues for the creation of common ground for all claimants. In this unfolding maritime drama, science offers all claimants the ability to monitor and to intervene.

Science diplomacy reveals at its core an ontological redefinition of this region. Knowledge sharing rather than naval vessels, commercial trawlers, advanced weaponry, and infrastructure, may prove to be the most powerful and essential tool to realizing peace and resolving territorial claims.

Diplomats need to take a page from scientific collaboration to better understand the myriad of South China Sea environmental challenges, since China’s success or failure in developing a blue economy will have implications for the rest of the globe.