Summary

Europe has been long preoccupied by the security of its gas supplies. The need to secure its import of hydrocarbons has been widely politicized and thus linked to hostile relations with major suppliers, namely with Russia. The fear of Russia switching off the gas tap Russia has overwhelmingly fueled the arguments of some European countries, mostly the newer EU member states that emerged from the former communist bloc, against new Russian pipeline projects. Pressure for developing alternative supply routes and the search for new suppliers, such as Azerbaijan, has intensified and led to a new natural gas supply project to Europe, bypassing Russia: the Southern Gas Corridor.

But has this Russian-centric view neglected other possible supply-disruptive actors and factors in Europe? The results of the Italian elections in 2018 reveal that Europe has more to worry than Moscow when it comes to securing its gas supply. The gas TAP might lie in Rome this time.

This article examines the prospects for the Trans-Adriatic Pipelines (TAP) within the context of the political-economic forces surrounding it, circumstances underlined by the recent declaration of new Italian minister of environment that the EU-backed TAP project is “pointless.” The article will then reflect on which logic will ultimately prevail: the geopolitical or the commercial one.

Background

Over the past two decades, politics and economics have often overlapped and the geopolitical approach to natural gas imports transcended the logic of trade. The gas weapon argument has been brought back to even higher levels of popularity after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the subsequent Ukraine crisis has raised intense political and policy debates in the EU related to the geopolitical misuse of gas infrastructure. Russia has been accused of using gas exports and pipelines to maintain its political grip on countries formerly in its sphere of influence.

Although a gas weapon argument largely ignores the complexity of mutual interdependence, following the repeated gas disputes between Russia and Ukraine and in the context of the more recent political tensions regarding Crimea and the conflict in Donbas, European countries and specifically the European Union made diversification of gas routes and suppliers a priority. Alternatives to bypass Russia, as well as Gazprom and its pipelines, were sought and various projects were imagined in the past years: developing a Mediterranean gas hub in Southern Europe, building LNG terminals, and constructing new gas pipelines. Among these, while some, like Nabucco were abandoned, one project has taken shape and been highly promoted as a viable alternative to Russia, as an effective way to enhance Europe’s energy security, diversify its supplies, and reduce dependency on a single supplier: the Southern Gas Corridor.

The Southern Gas Corridor represents a colossal undertaking. The project is meant to bring Caspian gas from Azerbaijan to Europe, aiming thus to reach a large number of markets through existing and planned pipelines, as well as through interconnectors. The ambitious project is worth US$40 billion, and stretching over 3,500 kilometres is a complex of several energy projects under one name. Among these, the connection to the Italian national gas grid in order to reach several European destination markets. There are three pipelines composing the Southern Gas Corridor, flowing from one another: the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP), in function since 2006 bringing gas from Azerbaijan to Georgia and Turkey; the Trans Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) inaugurated on 12 June 2018, crossing Turkey from its Georgian to Greek border; and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), the final leg of the Southern Gas Corridor, yet to be completed. TAP would take over from the Turkish-Greek border where TANAP ends, continue through Northern Greece, Albania and pass through the Adriatic Sea to Italy.

But will it do so?…

Analysis

The Southern Gas Corridor, an ambitious alternative to Russian gas imports to Europe, has followed the politicized rhetoric of past years and is thus expected to be countered by Russia which, in its own turn, will feel menaced by this new competitive project.

However, the final TAP is being threatened to be switched off not in Moscow, but in Rome this time.

Italy’s parliamentary elections in 2018 brought to power an anti-establishment Eurosceptic government led by Giuseppe Conte. Soon after taking office, the new environment minister, representing the 5-Star party, Sergio Costa, called the TAP project “pointless” and declared it was subject to revision, in a discussion with Reuters, under the motive of Italy’s falling gas demand.

Costa’s downplay of TAP came shortly before prime minister Conte’s declaration at the European Summit in Brussels at the end of June, expressing Italy’s opposition to the automatic renewal of sanctions against Russia. A (geo)politicized discourse in Europe might rush into expressing concerns regarding the Euroscepticism of Italy’s new government, and might connect its position on sanctions against Russia to the possible decision of blocking TAP, a major EU-backed project seen as a competitor for Russian energy interests in Europe.

But could it be that energy transcends politics? And might there be different motivations behind the political discourse? Will economic cooperation prevail over political competition?

Italy imports approximately 90% of its natural gas, with Russia being the main supplier (51%), followed by Libya, Algeria, Netherlands, and Norway. Contrary to minister Costa’s declaration, Italy’s gas demand increased in 2017 in relation to the previous years, although it is still at lower levels compared to the peak of 2010. With Netherlands’ plans to shut down its gas field at Groningen by 2030, Italy will lose 8% of its gas import supply, while gas demand is forecast to remain on a steadily ascending path. Alternatives such as LNG imports might prove too costly, while expectations of an extension of the Russian-backed Turkish Stream pipeline that would reach the Italian shores would have equal right to raise the same concerns voiced by minister Costa today: uselessness of investment and environmental damage.

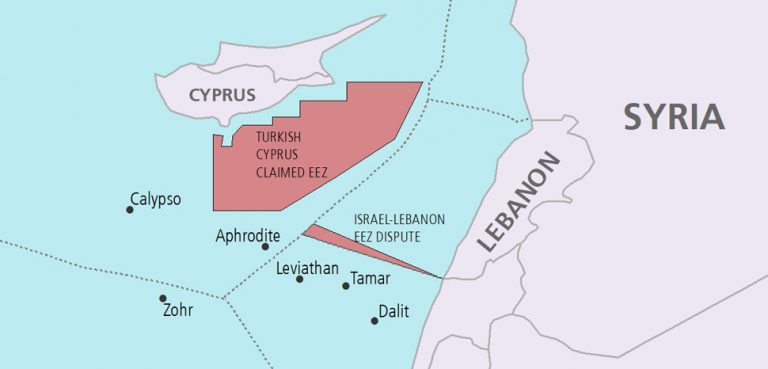

Moreover, a geopolitical black-and-white approach to the position of the Italian government, expressed through the TAP project, and seeing Italy taking sides between the EU and its partner Azerbaijan, on the one hand, and Russia, on the other hand, would be limited. The new government in Rome might indeed use TAP as a statement of their increased independence from the Brussels decision-making machine. But, as John Roberts, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center writes, the irony is that “the Russians may want to save the project” themselves. This is because, at present, Azerbaijan has the capacity to supply only half of the gas to be transported through the Southern Gas Corridor (6 out of the 12 bcm destined for Turkey and 10 out of the 20 bcm destined for European markets). As a result, Gazprom does not exclude the possibility of shipping Russian gas through TAP, though in the more distant future, Azerbaijan would like to see other producers supplying the Southern Gas Corridor: Iran, Israel, Turkmenistan and Cyprus. Politics might dominate the discourse, but it is likely that economic interests will also weigh heavily in the final decision of the Italian government.

And, last but not least, as Franco Pavoncello, a professor of political science and president of John Cabot University, quoted by Reuters, put it, “[v]irtually no Italian government has survived five years[…]”. And thus TAP might be delayed but not necessarily irreversibly side-lined.

**This article was originally published on July 3, 2018.