Summary

On 20 July, Cyprus marked the 44th anniversary of the Turkish military occupation of the Northern part of the island, which followed the Cypriot Greek-supported coup of 15 July, 1974. On the occasion, the Greek Minister of Defense, Panos Kammenos, quoted by Kathimerini, assured “[…]the Greek people, the Greek nation, whether here in Cyprus or in the motherland, that the armed forces are ready to tackle any threat.” The 1974 events led to the establishment, in 1983, of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, a de facto state recognized only by Turkey.

One of the protracted conflicts of Europe, the Cyprus conflict has defied resolution over the past four decades. Yet, until recently, it remained rather latent and attracted little attention outside the United Nations and the main state actors involved: Cyprus, Turkey, Greece, and Britain, the last three being Cyprus’ guarantor powers under the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee.

However, Cyprus has once again taken center stage in the geopolitical debates surrounding the Eastern Mediterranean, fueled by vivid discussions of possible new resource wars in the region, and the evolving role of Turkey. But what happened to trigger this change? First of all, Cyprus struck gas, twice: in 2011 and in 2018. Second, the Cyprus peace talks, led by the UN, collapsed dramatically in 2017 and left the international community in a state of pessimism regarding a possible reunification of the island. And third, Turkey decided to play a more assertive role in the regional energy game.

So what drives the Cyprus natural gas issue? Does it fall under the complex network of gas-conflict-cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean? Or is it a consequence of Cyprus’ ongoing division, amplified by the involvement of the two regional competing actors, Turkey and Greece?

Background

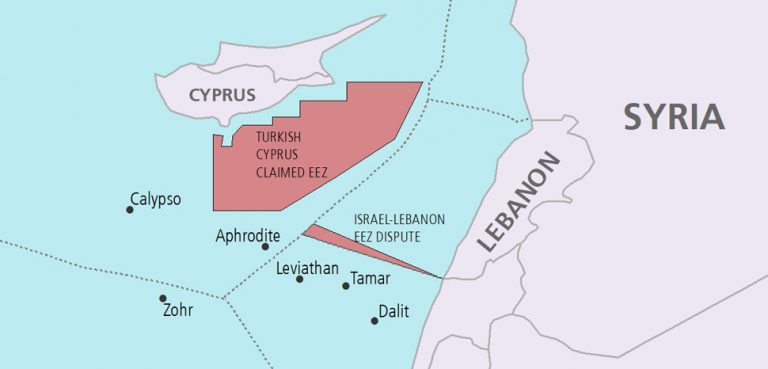

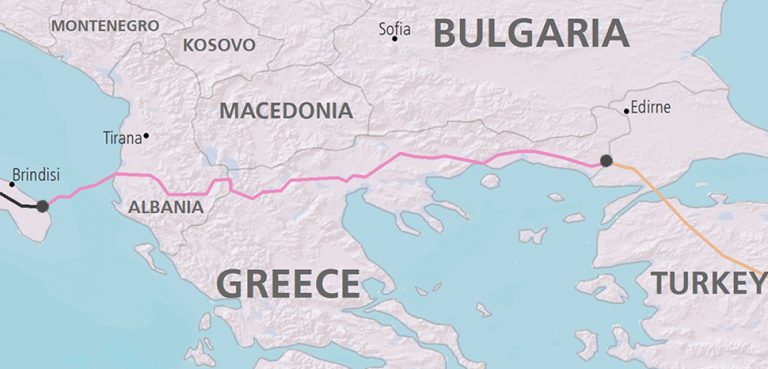

Gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean were only recently discovered and remain largely underexplored, with their total actual size yet to be evaluated. Out of these, five major discoveries stand out: the Tamar and Leviathan fields, discovered in 2009 and 2010; offshore Israel (with an estimated capacity of 282 bcm and 621 bcm of gas respectively); the Aphrodite field, discovered in 2011 off of Cyprus (with 128 bcm); and the 2015 major discovery off the cost of Egypt, the Zohr field, which holds the largest capacity in the Eastern Mediterranean with an estimated of 845 bcm of natural gas. The discoveries have aroused the interest of European countries looking for supply alternatives outside Russia, as well as of the energy companies. As a result, negotiations, predominantly bilateral, have been launched between various countries of the region. Examples include the €12 billion deal for Egypt to buy gas from Israel’s Tamar and Leviathan fields and the tripartite memorandum of understanding between Cyprus, Greece, and Israel to build a gas pipeline to Europe.

Turkey Steps into the Eastern Mediterranean Energy Game

But the waters of the Eastern Mediterranean really started to simmer when, on 8 February 2018, the Italian company Eni and the French company Total announced a breakthrough gas discovery at the Calypso block off the Cypriot coast, estimated to be comparable as size to the giant Zohr field. Just three days later, the Italian Eni drill ship Saipem 12000 was stopped by Turkish military vessels on its way to a gas drill position in the Block 3 of Cyprus’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The incident gave rise to an intense exchange of mutual accusations and diplomatic declarations; old and new tensions surfaced around the Calypso discovery and triggered a plethora of geopolitical and economic warnings about a new resource war on Europe’s doorstep. Outside analysis focused on the complex web of geopolitical competition and conflicts around the Eastern Mediterranean, and the focal point of concern became, this time, Turkey.

Turkey’s February military intervention in Cypriot waters raised fears that recent gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean would worsen pre-existing tensions in the area, potentially creating new conflicts driven by competition over the newfound resources. Concerns were fueled by a series of reciprocal warnings, days after the discovery was announced, mostly between Turkey and Greece, and by clashing declarations at the highest political level. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan warned Greece, Cyprus, and foreign companies that, by continuing the gas drilling off the coast of Cyprus, they are violating Turkey’s sovereignty. He went on to announce that “[Turkish] warships, air force and other security units are following developments in the region closely with the authority to make any kind of intervention if necessary.”

Turkey’s election campaign in June took it one step further. In May, Turkey launched its first drilling ship, named Fatih after the Ottoman Sultan Fatih Mehmet, which was expected to be dispatched to drill for gas in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Turkey’s ambitious energy plans marked by this event were highly symbolic. Turkey’s energy minister, cited by Cyprus Mail, compared, much to the concern of Cyprus and Greece, the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul with the launch of Fatih: “The conquest of Istanbul opened a new era in world history and the deployment of the first drilling vessel marks the beginning of a new era in Turkey’s oil and gas drilling objectives.”

If the timing of the launch was controversial, the event itself was hardly a surprise. It was meant to support Turkey’s plans to become a global player in the oil & gas field, and to reduce its high hydrocarbons dependence. The launch was in following with the country’s National Energy and Mining Policy, announced in April 2017, which focused on the mobilization of domestic resources and greater diversification. But it was news of a giant discovery in the Calypso gas field in 2018 that fueled new attention and ambition, much more so than the impact of the discovery of modest reserves in the Aphrodite field in 2011. What raised concerns from Greece, Cyprus, and their European Union partners was the connection between Turkey’s official stance against drilling offshore Cyprus, backed by its military presence, and the political discourses regarding Cyprus during Turkey’s June elections. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP)’s electoral ally, the ultranationalist National Movement Party (MHP), favors a hardline national security approach and, according to Sinan Ülgen from Carnegie Europe, it regards any Cyprus deal as treason. Greece and Cyprus’ fears were further aroused by an MHP electoral clip depicting Cyprus as a Turkish territory.

These new tensions came to complement existing concerns between the countries of the Levantine basin, notwithstanding the Syrian war, with Lebanon and Israel disagreeing over the delimitation of their EEZ, Israel and Turkey fighting over the Gaza issue, and Egypt, Cyprus, Greece, and Israel managing to forge a cooperative block, without Turkey, in the Eastern Mediterranean.

But is this just a matter of energy geopolitics, or is it a political issue stemming from Cyprus’ ongoing division?

Cyprus: A History of Division

In 1974, radical Greek Cypriots and troops from the Greek junta in power in Athens organized a coup and declared the unification of Cyprus with Greece. As a consequence, Turkey, one of the three guarantors of Cyprus (along with Britain and Greece) sent troops with the declared intention to protect the Turkish Cypriots. Inter-communal violence broke out across the island, with thousands ending up dead or disappeared on both sides. In 1983, the Turkish Cypriots declared the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and established their parallel administrative and political system. In 2017, international efforts to reunify the island, mediated by the UN, collapsed dramatically at the Crans-Montana talks. The Greek community, supported by Greece, refused to accept a federal Cyprus with Turkish troops on its soil and Turkey’s unilateral right to intervene, while the Turkish Cypriots, backed by Turkey, could not settle for the withdrawal of the approximately 30,000 Turkish troops still stationed in the North.

Turkey is the only country to have ever recognized the Northern entity while, at the same time, Ankara refuses to recognize the existence of the Republic of Cyprus (the Southern part). This is important for Turkey’s plans to start its own drilling in the Eastern Mediterranean, and it has major implications for Cyprus. In addition to not recognizing Cyprus, Turkey applies its own interpretation of international maritime law (contrary to the generally accepted UNCLOS – United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea). According to this individual interpretation, national territories have continental shelves up to 200 miles while islands are limited to territorial waters up to 14 miles and thus, for Ankara, Cyprus is an island with no rights to a continental shelf. In Turkey’s view, Cyprus has no legal right to declare an EEZ, and all agreements concluded by the Greek Cypriot authorities with international companies are legally invalid.

As a consequence, Turkish authorities accused Cyprus and the international companies drilling in the Block 6 and Block 3 off the coast of Cyprus of violating the sovereign rights of Turkey (which considers its own EEZ to extend to the blocks south of Cyprus) and of Turkish Cypriots. Moreover, in 2011, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus awarded in its own drilling rights for Block 3 to the Turkish company TPAO. Before the June elections, Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, quoted by Ahval, declared that the Cyprus-Egypt agreement to delimitate the EEZ between the two countries was “null and void,” violating the “inalienable rights” of Turkish Cypriots to “benefit from the island’s resources.”

The Republic of Cyprus offered a rather swift diplomatic response, being assertive regarding its rights as protected by the international law, but also stressing, through the voice of President Nikos Anastasiades: “the necessity of avoiding anything which could escalate.” The government’s spokesman Prodromos Prodromou linked the situation to the Turkish electoral climate and declared that Cyprus will avoid letting itself be pulled into the spiral of resulting tensions. The Greek Cypriots refuse to consider any agreement with their Turkish Cypriot counterparts regarding the possibility of joint exploitation of hydrocarbons unless a deal regarding Cyprus is reached first. The immediate prospects for such a deal however collapsed at Crans-Montana last year.

But what about the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus? The media focused overwhelmingly on the reactions of the main recognized actors and international players, but ignored the response of the element of discord itself. Kudret Ozersay, the foreign minister of the unrecognized entity, adopted a rather tempered line that echoed the South, declaring: “We aim at cooling down the waters, not warming them up.” However, the entity’s representative took a firm stance regarding Northern Cyprus’ determination to drill for gas with or without the Greek Cypriots: “I believe we will soon enter a period when everyone will see that nothing can be done in the region without first having the consent of the Turkish Cypriot people.” The president of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Mustafa Akıncı also called for a joint Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot committee to deal with the natural gas issue, linking the efforts in the gas cooperation to the future of a peaceful Cyprus, and accusing the Greek Cypriot leadership of refusing to share power and resources.

Looking Ahead: Gas for Cooperation or Conflict in Cyprus?

Despite the more virulent reactions and declarations of Greece and Turkey surrounding the Cyprus issue, it is to be noted that the Cypriot authorities, both the ones in the Republic of Cyprus, as well as the unrecognized ones in the Northern part, have chosen a more diplomatic voice in order to express their intentions and avoid further escalations as they exploit resources that both consider to be rightfully theirs notwithstanding the potential for future joint exploitation. Nevertheless, both parties continue to link the possibility of economic cooperation with finding a political solution to the protracted conflict that has divided Cyprus since 1974. Both Greek and Turkish Cypriots have expressed fatigue with failed negotiations over time, and it is in their interest to avoid a backslide toward conflict or a clash between other regional actors, as this would ultimately impede their successful exploitation of natural gas reserves.

Previous instances of cooperation in the energy field do exist between the South and the North. In 2016, their respective electricity networks were joined into one island-wide network and discussions for a further subsea link between Cyprus and Turkey’s electricity grid were launched.

Nevertheless, in the case of Cyprus, it might be that economics follow politics rather the other way around. Although instructive examples of past cooperation, both inside and outside the energy field, already exist, solving the chronic political issues between the South and the North and reaching a settlement of the conflict might be the better incentive for a peaceful and fruitful exploration of gas reserves. Should this ever come to pass, Cyprus would be able to play a central role in the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as on the wider European energy stage.

This article was originally published on August 20, 2018.