As the name indicates, geopolitics is a hybrid analytical discipline that combines elements of both natural and social sciences in order to explain the patterns of political behavior in contexts shaped by spatial conditions. One of its key assumptions is that geography is arguably the most important factor that defines the national power of states. This relevance stems from its relative permanence over time. After all, kingdoms and empires come and go, but rivers, oceans, mountains, deserts, jungles, valleys, barriers, chokepoints, waterways and corridors remain.

Geography does not refer only to locations, resources or territorial extension per se. Above all else, it has to be envisaged according to the instrumental strategic value of its properties and features in terms of military action, national security, economic development, commercial exchange, diplomatic considerations, demographic dynamics, socio-political expectations, historical ambitions, and cultural ideas, amongst other factors. Accordingly, national states can be seen as living organisms that seek to adapt and improve their circumstances as much as possible in order to satisfy their vital needs.

However, in an environment where competing claims and scarcity are commonplace, some of those imperatives are mutually incompatible. Hence, the zero-sum logic of relative gains dictates that there will always be winners and losers in any conceivable situation. One of the results of this reality is that territorial expansion is often a phenomenon in which the interests of a stronger actor prevail over those of a weaker counterpart. That explains how borders are constantly being redrawn.

Contrary to what is commonly believed by some international relations scholars and practitioners, these general principles are far from obsolete. The most recent example is of course the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula by Russia. Furthermore, clashing geopolitical projects are fueling growing strategic competition in places like the Arctic and the South China Sea. Tellingly, similar geopolitical calculations sparked US President Donald Trump’s interest in purchasing Greenland last year. More recently, it looks like an interesting case is unfolding in the Middle East. Considering the region’s endemic volatility, a closer analysis is thus in order:

Understanding Israel’s geostrategic rationale

Due to both its position in a hostile environment and its small territory, Israel has seized valuable opportunities to increase its vital space more than once. As a result of its crushing victory over Arab armies in the Six-Day War, Israel took the Golan Heights from Syria, the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt and the West Bank from Jordan, mainly in an attempt to strengthen its defensive buffers.

For all intents and purposes, the Golan Heights have been fully absorbed by Israel, regardless of what the ‘international community’ has to say about it. On the other hand, the Sinai Peninsula was returned to Egypt as a consequence of the bilateral Peace Treaty that normalized diplomatic relations between the countries. In contrast, the status of the West Bank remains a contentious issue and one of the core controversies of the so called Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Israelis regard such territory as the biblical “Judea and Samaria” (as it is often called in Hebrew), whereas Palestinians claim the land as the cornerstone of a hypothetical Palestinian state.

From the perspective of Israeli national interests, it makes sense to establish a more direct control of the West Bank for several reasons:

The land is suitable for growing crops like olives, citrus fruits and vegetables, as well as for the production of beef or dairy. Needless to say, it would provide arable land for Israel’s booming and high-tech agricultural sector.

It has deposits of water resources, including both the Jordan River and the mountain aquifer. It must be borne in mind that securing access to fresh water is a must for a country prone to experience high levels of water stress.

The expansion of existing settlements would provide more affordable housing for Israeli citizens, particularly for those who are not very affluent.

It would increase Israel’s strategic depth and the security perimeter around its heartland. Some senior Israeli military commanders believe this imperative is already being met by the existence of Jordan, considering it operates as a buffer state. Nevertheless, relying on the goodwill of others –or taking for granted their long-term stability – can be perilous in the ruthless Levantine geopolitical chessboard.

A stronger Israeli presence in the West Bank would mean that the idea of sharing Jerusalem as the simultaneous capital of two states would be rendered ludicrous.

The move would boost Prime Minister Benjamin’s Netanyahu’s career, especially considering his closeness to hawkish nationalist forces and the hardline branch of religious Zionism. Although he is a pragmatist whose concerns are rather worldly, the support of those factions has been crucial for his successive ruling coalitions. So if manages to score a major victory, his legacy would be compared to that of legendary Israeli statesmen like David Ben-Gurion and Menachem Begin.

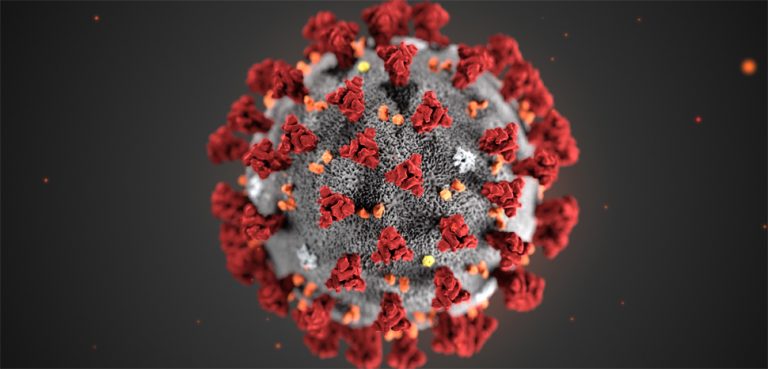

In other words, the annexation would serve Israel’s geostrategic agenda. Furthermore, an international context in which the fallout of the ongoing global coronavirus pandemic is going to be the highest priority for many national states for at least the rest of the current year represents a window of opportunity waiting to be harnessed in order to advance the implementation of the aforementioned annexation plan. It is a moment that encourages boldness. For instance, even recent critical geopolitical developments – like the targeted assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani in a drone strike launched by the Pentagon – have been all but forgotten amid the disruptions of COVID-19.

A balance of power speaks louder than words

In order to foresee likely courses of action, interests have to be taken into account; but the importance of assessing capabilities cannot be overlooked. In this case, it can even be argued that – in terms of national power – Israel is stronger than ever before. After all, it is an island of geopolitical stability in a region engulfed by turmoil. Likewise, Israel has recovered the full diplomatic support of the United States under the Trump administration, as shown in the relocation of the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem a couple of years ago. Moreover, Israel is still the top recipient of US military assistance. Moreover, it has sought closer ties to both Russia and China, great powers that regard Israel’s high-tech productive sector as a promising asset. In other words, Israel can rely on Washington’s geopolitical patronage while remaining on friendly terms with both Moscow and Beijing.

Moreover, Israel has developed its own military-industrial complex that manufactures state-of-the-art weaponry and hardware that is highly competitive on the global arms market. The Israeli military has adapted its doctrine and operational readiness so that it can fight in both conventional and unconventional battlefields. Likewise, Israeli civilian intelligence and security agencies –including the Mossad and the Shabak – are amongst the most competent in the world and their expertise is envied by similar services elsewhere. Another fact that deserves to be emphasized is the role of Israel’s nuclear arsenal as a powerful strategic deterrent.

Concerning economic might, Israel is a developed industrial economy. It has comparative advantages regarding aerospace, ICT, advanced electronics, machinery, medical equipment, renewable energy, bio-technology, agricultural production and software. According to the Atlas of Economic Complexity, Israel is a more complex economy than certain developed countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, Canada and Australia) and emerging markets (India, Poland, Turkey and Brazil).

In contrast, the Palestinians’ geopolitical position is compromised. During the Cold War, their cause was backed by states that were eager to sponsor secular Arab nationalism (the ideology embraced by Yasser Arafat and his generation of Palestinian leaders). However, after the bilateral peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, the decline of Arab nationalism – in military, political and economic terms – and the fateful demise of the Soviet Union three decades ago, the Palestinians have been left in a state of geopolitical orphanage – a dire condition in a region that constantly attracts the involvement of extra-regional powers.

Furthermore, the Palestinians themselves are internally divided. Whereas areas “A” and “B” of the West Bank are governed by the secular and nationalist movement known as Al-Fatah, the Gaza Strip has been ruled by the Islamist militant group Hamas since 2007. This political schism has even provoked violent clashes. As a result, there is no single unified entity that can speak for them or negotiate on their behalf. So far, reconciliation efforts – brokered by Arab states – have taken place but no conclusive agreement has been reached.

On the other hand, the Palestinian leadership has alienated many Arab countries. First, the active presence of Palestinian militias in places like Jordan, Lebanon and Egypt triggered tragic incidents of socio-political and military violence. Later, Yasser Arafat sided with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq even though the armies of many Arab states – including Bahrein, Morocco, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Syria and the UAE – decided to participate in Operation Desert Storm.

Additionally, Hamas flirtatious attitude towards Iran – a country that is interested in supporting the Palestinian cause as a conduit to advance its geopolitical agenda – is viewed with deep distrust in many Arab capitals due to Tehran’s regional aspirations and its various militant proxies. However, Hamas has also angered the so-called ‘Axis of Resistance’ because some of its fighters joined forces with Sunni extremists against the Al-Assad regime in Syria, even though it is heavily backed by Iran and Hezbollah.

Last but not least, the Palestinian economy is exceedingly fragile. It depends mostly on primary activities, the manufacture of handicrafts and tourism. It has a growing IT sector but its rise is organically linked to outsourcing commissioned by Israeli companies. Likewise, Palestinian territories receive a great deal of foreign aid but it is unclear if those resources are being used to foster development. Some economists have even argued that a considerable proportion of that money ultimately goes to Israel, since it acts as provider of goods and services demanded by Palestinian consumers.

In light of the above, it is reasonable to assert that there is an asymmetric correlation of forces which overwhelmingly favors Israel. In blunt terms, this reality undermines the prospect of implementing a two-state solution anytime soon.

What to expect

Israel might be operating under the assumption that it can implement the annexation of Area C of the West Bank – roughly equivalent to the surroundings of the Jordan Valley – and experience little in the way of international pushback. After all, the Palestinians are unable to retaliate in any meaningful way. A noteworthy recent precedent pointing in that direction was the relocation of the US embassy to Jerusalem. Even though the measure was highly controversial and the risk of violent protests erupting as a result of popular anger was real, it was all a matter of smooth sailing in the end.

Palestinian militant groups might respond with shootings, beatings, firefights, skirmishes, rocket attacks and perhaps even suicide bombings. That can certainly cause the deaths and injuries of Israeli soldiers and civilians but, in the grand scheme of things, neither option has the power to compromise the national security of the Israeli state or cripple the continuity of its economic activities. Yet, Israeli security agencies have warned about the prospect of a ‘third Intifada.’ Needless to say, a wave of unrest would be a strategic distraction that might diminish Israel’s ability to deal with much more dangerous regional threats. If the aftermath of the backlash were too nasty, that might derail Netanyahu’s plans for his political legacy.

On the other hand, aside from simple rhetorical lip service paid to the Palestinian cause, though some Arab states might feel genuine empathy for their Palestinian brethren, it remains doubtful that they would be willing to go to war over these feelings. They are certainly not ardent Zionists, but many have come to believe that Israel is a state whose limited ambitions – going by traditional Middle Eastern standards – do not jeopardize regional stability. What’s more, Israel can be a reliable security partner and perhaps even a potentially attractive business partner in the foreseeable future.

Jordan could be expected to experience the heaviest impact from a sudden annexation, especially considering it might be flooded by large numbers of Palestinian refugees. Yet, there is little Amman can do about it, aside from diplomatic complaints. It would also be detrimental for Jerusalem to unnecessarily burn the incipient ties it has developed with Arab states.

Moreover, the newer generation of Arab leaders tend to be focused on Iran, which some view as a hostile actor intent on becoming the region’s premier power. Tehran’s overt and covert involvement in operational theatres like Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, and even the Arabian Peninsula itself in order to protect its allies, further its geostrategic agenda in the name of ‘anti-imperialist struggle’ and attempt to overthrow its rivals is seen as profoundly troubling. Since Tehran also happens to be Israel’s top geopolitical rival in the region, there is a security incentive for Jerusalem and Arab capitals to collaborate in order to contain Iranian influence. Geopolitics indeed has the power to make strange bedfellows.

Another stakeholder whose reactions have to be calculated is Iran itself. Until not long ago, Iranian influence had been seemingly growing and Tehran’s grand project of establishing a ‘Shiite Crescent’ from Western Afghanistan to the Mediterranean coast of Lebanon looked to be within reach. However, the Persian nation has since suffered some severe setbacks. Falling oil prices have been disastrous for its energy-reliant economy, and sanctions imposed by Washington have exacerbated the situation.

Iran has invested a large amount of resources, money, and manpower into the Syrian civil war. Moreover, the country is still suffering heavily from the effects of the current coronavirus pandemic and tensions persist between the religious authorities and Iranian youths, who are broadly in support of liberal reforms.

Therefore, it is reasonable to wonder if Iran has the ability or the appetite to engage Israel in a direct confrontation right now. It is clear that Tehran is not entirely powerless. Quite the contrary, Iran has two important cards to play in the event of a conflict. One is the reactivation of its militant proxies in operations launched against Israel along several fronts. Another is the use of its covert tentacles and psychological warfare tactics in order to generate the critical mass that would be needed to unleash uprisings in many Arab countries, whose governments can be portrayed as corrupt, cowardly and/or duplicitous. Provoking regime change might thus be a game changer that alters the regional balance of power in a very disruptive way.

If Israel decides to go ahead with the annexation, it will do so in the knowledge that the move will be regarded as illegal under international law. Yet, since there is no supranational authority that has the power to enforce said law, then ground-level realities will determine the course of events. An overriding question that would need answering is what to do with the Palestinian Arabs who suddenly find themselves under direct Israeli sovereignty. One option would be to provide some sort of compensation for those that decide to leave. Another solution would be to offer citizenship at some point, but the conditions and parameters of such an unconventional solution would have to be carefully weighted, designed, and implemented by policymakers given Israel’s demographic balance and self-image.

Concluding thoughts

It appears as though Israel’s annexation of the West Bank will be a fait accompli sooner or later. Based on the complexity of plausible ramifications, it is likely that such a project will be undertaken as a gradual process rather than as the result of one broad stroke, in order to forestall some of the most counterproductive scenarios. One way or another, geopolitical factors suggest that, in the not-so-distant future, there will be only one state between the river and the sea.

Many centuries ago, the Athenian historian Thucydides wrote that “fairness, as the world goes, is only a matter between equals in power; the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” But he didn’t stop there. Thucydides also stressed the importance of cautious restraint as a sensible expression of power. These lessons are still valid when it comes to understanding international politics in the 21st century, especially in circumstances where the stakes are incredibly high.