The Arctic Circle’s once inhospitable environment is changing dramatically, and the geopolitics of the region is shifting with it. Russia planted their flag on the seabed of the North Pole in 2007 and have been building up military installments ever since. China has been interested in the Arctic since the 1980s, and in January this year, published its first white paper on the region. President Trump, with his “America First” campaign and denial of global warming, has left behind various vacuums for other nations to pursue their interests. This is particularly true of the Arctic.

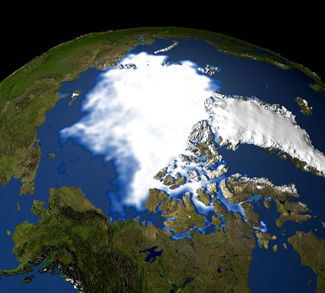

The Arctic’s littoral nations consist of the United States, Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Iceland, and Russia. Along with Sweden and Finland they form the Arctic Council, an international institution that was created in 1996. The Arctic Council also comprises of 13 observer nations. Besides attending meetings, these states are required to contribute to the group, and can propose projects and present written statements. Following decades of interest in the region, China became an observer in 2013. A major focus of the Council is the melting icecap, as it not only affects the coastal nations, but the rest of the world due to global climate change and the search for energy resources.

The CAA has established two polar bases, one on Svalbard Island and the other in Iceland.

China has been interested in the polar icecaps since at least 1981, when it established the Chinese Arctic and Antarctic Administration (CAA). The department has five divisions: general affairs, policy and planning, operations and finance, science programs, and international cooperation. It has a training base in Heilongjiang Province, in northern China. The CAA has eight objectives, including national strategies and laws, undertaking expeditions, science projects, and international cooperation. Besides extensive Antarctic activities, the CAA organized six Arctic scientific expeditions from 1997-2014. Additionally, it established an Arctic base in Norway and has been gathering data there since 2004.

The CAA has established two polar bases, one on Svalbard Island and the other in Iceland; next it hopes to set up a new base in Canada. The organization has a largely scientific focus. Four Chinese universities, in cooperation with six Nordic ones, created the China-Nordic Arctic Research Center in 2013.

China’s invitation to the Arctic Council paved the way for its current engagement in the region, but there’s another major initiative drawing the Middle Kingdom to the far north.

The One Belt One Road Initiative is China’s new Silk Road and the Ming Dynasty maritime push combined. It is the world’s largest economic endeavor, potentially involving 60 nations and more than 4.4 billion people. Chinese President Xi Jinping figuratively discussed it in his 2015 statement at the UN. A major component of the speech was his promise of “win-win” situations all over the world. As planned, OBOR would open unfettered pathways to Europe, Africa, and ultimately Latin America. Scott Kennedy of CSIS believes the OBOR will see promote economic and cultural cooperation across Asia. In January, China released its new Arctic policy white paper, in which it self-identified as a “near-Arctic State.” Beijing has also extended OBOR funding to support a Polar Silk Road.

China is clearly setting some highly ambitious goals in terms of economic cooperation, and in doing so it is staking new claims worldwide – claims that are making some democracies uneasy.

China’s Arctic Policy

China’s Arctic Policy has five main objectives under which ‘respect, cooperation, win-win results, and sustainability’ will be pursued. The plan is to further China’s understanding of the Arctic via scientific and climate change research, ‘using Arctic resources in a lawful manner, to participate in international cooperation, and to do all of this peacefully.’ Thus far, the Polar Silk Road seems comparable to OBOR.

Beijing has deemed scientific exploration and research to be a priority, utilizing multi-disciplinary sciences involving but not limited to biology, geology, economy, meteorology, and chemistry.

The new Arctic policy’s secondary objective involves climate change. The country’s scientists are trying to find ways to preserve the Arctic environment, and perhaps improve it in the face of growing climate pressures.

Finally, China’s Arctic policy promises to maintain all legalities concerning the Arctic. The government pledges to abide by UNCLOS in not claiming sovereign rights and respecting EEZs of littoral nations. China will continue its scientific endeavors, as well as newfound joint ventures in energy extraction, in full accordance to previous and current arrangements and treaties.

Responses to China’s Arctic Policy

Sherri Goodman is a Senior Fellow at the Wilson Center and former U.S. Deputy Under Secretary of Defense in environmental security. In a recent interview, she touches down on how China’s Arctic Policy responds to global warming:

China clearly recognizes that that climate change is happening…so they make no bones about wanting to confront it and adapt to it. In fact, they’re using it, in many ways, as a source of strength. It is in part what spurs their interest in the Arctic because there is greater access to the region and the energy and mineral resources that are just now becoming ice-free.

In Svalbard alone, China has more than 500 scientists, but Greenland and Iceland are what interest them most in terms of OBOR. Beijing is taking advantage of this opportunity to capitalize on new and potentially extensive natural resource deposits. If properly embraced, this could be a tremendous business opportunity for US companies.

At a recent Wilson Center Ground Truth Briefing, the gathered experts had mixed feelings on China’s foray into the Arctic. A retired ambassador for oceans and fisheries, David Balton, claimed that Chinese involvement in the Arctic was not yet controversial, but he warned that Arctic nations should be wary as China asserts itself in the region. He was also unsure if littoral nations would welcome Chinese investment. Robert Daly, Director of the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States noted: “the [Chinese white paper] also speaks continually about a ‘shared future for mankind’ … This is really Xi’s most important phrase for framing China and China’s rise – the role it wants to play in the international order – as benevolent.”

There was some agreement among participants that, whatever China’s ultimate intentions in the Arctic, the United States under President Trump is not rising to meet them with any new Arctic policy from the U.S. side.

China’s Arctic policy promises to maintain all legalities concerning the Arctic.

Two others points from the briefing are significant. Michael Sfraga, director of the Polar Initiative explained, that as the region warms, more opportunities will open, and the U.S. should welcome this, but be cautious. The second is from Captain Lawson Brigham, a professor of Geography and Arctic Policy, who noted that the word ‘military’ is not used throughout the entire white paper.

China will not be turning away from the Arctic any time soon. Clearly it is determined and ready to deepen its involvement in the region on multiple fronts. Taking into account these ambitions, however lofty they may seem, the U.S. could read this scenario in two ways: as a cooperator or a competitor. Which one it chooses remains to be seen.

Many nations, regardless of their latitude, are involved in scientific research in the Arctic. The shifting geopolitics of the region is something to watch, especially since many US allies are already participating and investing, whether littoral or not. China’s goals in the north are not a concern to the United States, nor any of the Arctic nations – at least for now. Until proven otherwise, maybe the U.S. should try engaging with China and forging new scientific and financial joint ventures in order to explore this great unknown together.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.