This article is first in a two-part series. Part two can be found here.

The recent controversy surrounding Saudi Arabia and its political-financial establishment’s alleged role in the 9/11 terrorist attacks has produced massive amount of commentary in mass media outlets and on online forums. And this in turn has begun to manifest in bilateral tension between the governments of the United States and Saudi Arabia.

The 9/11 families want to file a lawsuit against Riyadh, arguing that the Saudi government was complicit in the al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington DC. The lawsuit was dismissed by New York federal judge George Daniels in September 2015 because of the insufficient evidence provided by the plaintiffs. The case was unable to overcome Saudi Arabia’s sovereign immunity. The 9/11 families still want to sue on the grounds of certain politically-connected Saudis providing aid to the al-Qaeda operatives. 15 out of 19 hijackers were Saudi nationals.

The Saudi government responded to the lawsuit by threatening to sell $750 billion worth of treasury securities and other American assets, in attempt to throw the US economy into utter chaos. However, President Obama stated that he is opposing the bill that would allow the lawsuit to proceed on the grounds that its passage would potentially allow other sovereign states to make similar moves against the United States government. However, judging from the Saudi bluff, the accusation of complicity must have hit quite a nerve in Riyadh.

It has been adamantly asserted by those involved in the prosecution of implicated suspects of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, such as former federal prosecutor Andrew McCarthy, that at least several of the high-ranking members of the Saudi establishment were complicit in the attacks. The controversy surrounding 28-page section in the massive 838-page 9/11 Congressional Report – at least a part of which the Obama administration is preparing for a possible release – is at the center of this contention (CIA director John Brennan is adamant that the cache of documents should remain secret). 9/11 complicity of some prominent Saudi figures would not be all that surprising. Credible NSA sources have indicated that some of the elements of the Saudi state have let more than mere sympathy find its way to al Qaeda projects. Indeed, the Saudi role in proliferation of extremist strain of Wahhabi ideology by exporting it via multiple channels is no secret and has been explored by analysts on Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

Another state that was in the cross-hair recently for alleged complicity in the 9/11 attacks is the Islamic Republic of Iran. In March 2016, the very same federal judge George Daniels – who dismissed the claim against Saudi Arabia back in September 2015 – awarded the 9/11 victims’ families $10.5 billion from Iran for its alleged role in the 9/11 attacks. It was a default judgment because the Iranian defense representative failed to show up in court. Although no 9/11 terrorist was an Iranian national, the accusation was that Iran allowed al-Qaeda operatives to pass through its territory without having their passports stamped, which made them easier to enter United States to conduct the attacks. Iran has also been accused of sponsoring al-Qaeda operations through Hezbollah, the Iranian intelligence proxy active in Lebanon.

Despite being portrayed to the general public as hostile and irreconcilable enemies, some noteworthy Sunni extremists and Shia extremists have collaborated extensively to achieve common ideological goals throughout their history. The 2011 Arab Spring that led to chain of overthrows of Western-oriented dictatorships was praised with passion by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who proclaimed that it was a stepping stone to ‘Islamic Awakening.’ This was despite the active force of these overthrows being Sunni organizations. One of the charges filed in Egypt against former Egyptian Islamist President Mohamed Morsi, who came to power after the 2011 revolution, was that of espionage. He has been implicated in passing classified Egyptian state secrets to the Teheran regime. This demonstrates the close nexus these Sunni Islamist and Shia Islamist entities enjoy. It also seems that Iran is determined to keep Saudi Arabia in check by grabbing initiative over the Arab Spring – especially by courting the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, which is against the corrupt Saudi regime.

This phenomenon of a Sunni-Shia nexus will be examined in time. Elements of the Saudi Arabian establishment, the Iranian state intelligence, and high-ranking al-Qaeda operatives were engaged in a triangular relationship. And the collaboration of these three entities was facilitated by a single figure – Hassan al-Turabi. Al-Turabi was a former Muslim Brotherhood ideologue that passed away – coincidentally also in March 2016. Al-Turabi facilitated this triangular relationship within an African sovereign state in which he was active. And that ever-unstable state, plagued with near constant civil wars, was the Republic of the Sudan.

Sudan: A Brief Geopolitical History

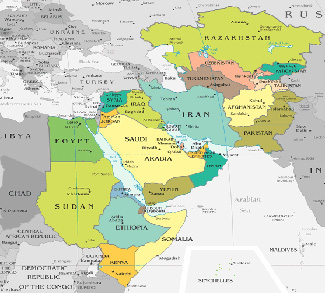

The Republic of the Sudan is currently the third largest sovereign state in Africa, after Algeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Sudan lost a significant amount of territory after the July 2011 cessation-independence of its southern region, leading to the formation of the Republic of Southern Sudan.) It is linked to Egypt to its north, not just by its territorial border but also by the life-giving Nile River. Nile is the river into which the two tributaries, White Nile (water sourced in Lake Victoria on the Tanzania-Uganda-Kenya border) and Blue Nile (water sourced in Lake Tana in Ethiopia), merge at the capital city of Khartoum. Sudan also is located by the geopolitically-significant Red Sea to its northeast. This links Sudan to the Arabian Peninsula on the other side of the Red Sea, a connection formed in the ancient times. This location also has linked Sudan to the global commerce propped up by the European Imperial powers, especially since the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869. One of the important features related to the Suez Canal is the maritime chokepoint of Bab-El-Mandeb, the strait linking the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden (and thus the Indian Ocean). Bab-El-Mandeb was fiercely contended over by the 19th century colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Italy, and all engaged in multiple regional interventions. Sudan is therefore geopolitically and historically linked indivisibly with European and MENA (Middle East- North African) regimes, and with their struggle for control over Egypt and the region in general.

Sudan is historically noteworthy for it being the location of the Kingdom of Kush (11th century BCE to 4th century CE) – a Nubian kingdom that even managed to briefly place Egypt under its control from 747 to 656 BCE until it was overthrown by the Assyrian Empire after a failed attempt to expand into the Middle East. Kush is said to be one of the earliest kingdoms to utilize iron smelting technology, receiving its inspiration from the Assyrians. The dissolution of the Kushite kingdom in the middle of the 4th century CE resulted in a political fragmentation into three Nubian states: Nobatia, Makuria, and Alodia. These three states were heavily influenced by various traditions of Eastern Christianity and practices of Eastern Roman Empire, especially during the reign of the Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565).

However, by late 7th century CE the region was starting to come under the powerful sway of the newly rising religion of Islam, when the Arab Rashidun Caliphate conquered Egypt in 641. After two fierce Battles of Dongola (642 and 652) involving guerilla-esque horseback tactics on the part of Nubians, the Arab invasion was successfully repelled; a treaty called al Baqt was struck between Nobatia and Islamic Egypt which established peace between the parties involved. This treaty was a rare exception in history of Islamic relationship vis-à-vis Christian regimes where the Islamic philosophical division of the world into Islamic and non-Islamic– that of ‘Dar el-Islam’ and ‘Dar al-Harb’ – was set aside and existed in relative peace.

Makuria annexed Nobatia to its north under the reign of its King Merkurios in early 8th century, expanding its territorial hold. Although the Shia Fatimid Caliphate soon wrestled control over North Africa away from the Sunni rulers in 909, the new Ismaili Shia Caliphate and Makuria maintained peaceful relationship. Although the trade – which included not only natural resources but also human slaves– was maintained, tensions began to form due to rise of Saladin’s Kurdish Ayubbid dynasty (1171), which proceeded to take over the Fatimid Caliphate. After centuries of prospering, Makuria started on its path to collapse by the latter part of 12th century, partly facilitated by mass migrations of Bedouin tribes instigated by the Ayubbid dynasty. Then the Ayubbid dynasty was replaced by the Mamluk Sultanate (1250) and intervention in Makuria’s internal affairs intensified, due to regional situation of the time (such as Makuria’s inability to provide security in certain regions as stipulated by the Baqt agreement). By 1312 Mamluk invasion commenced and anarchy ensued in Makuria; the collapsing kingdom was integrated into the Muslim regime of Banu al-Kanz (1412). Alodia, the southernmost state, was able to hold off the Islamicization for a while, but was also ultimately Islamicized. Alodia was transformed into Abdallab Empire (c. 1480), and then was absorbed into the newly established Funj Sultanate of Sennar in 1504.

This chain of events between Islamic Egypt and the Nubian states in the Middle Ages would centuries later re-manifest into another geopolitical relationship involving a regime that will centuries later take over Egypt and draw other European empires into the region in a struggle for domination: Great Britain.

In 1820, the Ottoman Empire – which had conquered Egypt back in 1517 – destroyed the Funj Sultanate which had steadily expanded its control over the area for three hundred years and supplanted the control over the region of Sudan. Ismail, the son of Muhammad Ali Pasha the Ottoman ruler of Egypt, led troops and successfully conquered Sudan in July of 1821. It was now included in the dominion of the Ottoman Empire – soon to commence its slow decline– and ruled by governor-generals.

In the coming decades, Western powers intensified geopolitical intervention in the region directly related to security of Sudan: In 1835 the British Empire – or more specifically the British East India Company – constructed an outpost in Yemen on the Gulf of Aden as a coaling station. This useful location for maritime transit – and a paramount key in dominating the international trade – also came to function also as a prime location for linking Britain and India with telegraph cables decades later as part of the Imperial project. The importance of the outpost increased further after the construction of the Suez Canal in 1869 (which as we will soon see, led to direct British military intervention in affairs in the Khedivate of Egypt). In 1886 the portion corresponding to modern-day Yemen became Protectorate of Aden.

The construction of the Suez Canal had a revolutionary impact on the international commerce of the major European powers that can in no way be overstated. The French concluded a deal with Muhammad Said Pasha, Khedive of Egypt and Sudan, and launched its construction project in 1859. The canal was completed a decade later, under the rule of Khedive Isma’il, although with some setbacks due to British agitation of construction workers. Due to its completion, the European powers no longer had to sail around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa – a severe drain on resources and time – to engage in trade with Asia.

In the years after the completion of the canal financial problems erupted in the Khedivate. This crisis led Great Britain – then under the administration of Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli – to take control of the Suez Canal in 1875 and administer it jointly with the French. This was partly due to a geopolitical consideration. As a counter-Russian strategy in the Great Game, Britain stepped in to fill in the void left by chasms of decaying Ottoman Empire which originally functioned as a check against Russia. However this massive financial crisis also led the Khedivate to the brink of collapse. The Khedivate – and particularly in the area of its finance – increasingly came under the influence of the Anglo-French forces. Finally in 1879, the ‘Urabi Revolt’ ensued. The revolt was led by disgruntled and incensed nationalist masses under the command of Army Colonel Ahmed Urabi, who desired to overthrow Khedive Tewfik Pasha and terminate the foreign rule, thereby restoring non-Western Islamic rule over the Khedivate. Army revolted in 1881 and placed the Khedivate government under its control in February of the following year. This led to the Anglo-Egyptian War in summer of 1882, which ultimately ended up reducing the Khedivate to status of a protectorate. On June 11 of 1882, several thousand nationalist Egyptian protesters stormed the European quarters of Alexandria, engaging in mass violence in the city where Khedive Tewfik had relocated his court. The instigator of the violence has been debated, and Tewfik himself has been accused of artificially manufacturing this round of violence to discredit Urabi and reconsolidate his power over the Khedivate. Off the coast of Alexandria fleets of Anglo-French ships were present, due to promise made earlier in January to assist the Khedivate in case of security crisis. The British intervened in the crisis; the bombardment commenced on July 11. The British forces landed on Egypt, and after two major battles, authority was restored to Tewfik.

As we can see the opening of the Suez Canal led to one hot mess of chaos and violence in the Khedivate. At the same time it had made a tremendous geopolitical impact by making Bab-El-Mandeb also an indispensable maritime chokepoint. In classical geopolitics, there is no reason for a state – or alliance of states– to control every bit of the entire ocean to oversee or protect international trade. Having control over various chokepoints is enough to gain upper hand against adversaries, whether in form of rival states or non-state actors such as marauding pirates. It was not only to the British that this new Red Sea chokepoint was important. Soon the Italians joined in the geopolitical adventure by intervening in the region, albeit on the African side of the Gulf of Aden. The Kingdom of Italy established a settlement in 1882 in what is now Eritrea. The settlement was found on a strip of land originally bought by an Italian shipping company to use for a coaling station. (Securing coaling stations were all the rage among major powers at the time). The United States acquired Pearl Harbor in Hawaii as such, soon before which the kingdom was overthrown and dissolved in 1895.) A formal colony was later found on the settlement in 1890. Italian Somaliland was found also in 1889. The series of events soon led to tension with the Empire of Ethiopia, igniting the First Italo-Ethiopian War in 1895.

The French also entered the geopolitical fray, to the southeast of Italian Eritrea. The French signed treaties with the local sultans between 1883 and 1887, culminating in the establishment of Djibouti City, which became the capital of the new French Somaliland in 1896. The French backed the Empire of Ethiopia against Italy in the Battle of Adwa, the finale of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. As Great Britain and Italy exploited the region for maritime commerce, the France exploited the region for land-based commerce, linking Djibouti and Addis Ababa – the capital of Ethiopia – via Ethio-Djibouti Railways to foster export trade.

One of the side effects of the Anglo-Egyptian war of 1882 was rise of Islamic fundamentalism, as an alternate form of regime system to Khedive Tewfik’s corrupt, Western-sponsored regime. In fact, Urabi had warned the British that British intervention would cause Islamic radicalism to rise and that “the first blow struck at Egypt by England or her allies will cause blood to flow throughout the breadth of Asia and of Africa.”

This rise of Islamic fundamentalism occurred in Sudan with the rise of Mahdist movement. The Mahdist movement is essentially an Islamic messianic movement, and this was led by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had declared himself to be that very Mahdi in 1881 before the war, in the midst of the Urabi Revolt, to rescue Islam from the hands of corrupters of the religion. Although he was of Samaniya Sufi tradition, his ideology was heavily influenced by Wahhabism – which would later become a vector for Islamic radicalism sponsored by Saudi Arabia.

Ahmad’s Mahdist movement would work to establish puritanical Islamic state. The jihad campaign easily overran the Khedivate forces in Sudan. The British directly intervened merely to protect its strategic posts – especially the geopolitically significant Bab-El-Mandeb on the Red Sea. Some Egyptian expedition force was sent against the Mahdist forces. This, led by the ill-prepared Col. William Hicks, ended in utter disaster. The Khedivate essentially left the situation of the Sudan in the hands of the self-proclaimed Mahdi for several years due to the budget cuts resulting from massive financial austerity measures that were being imposed in Egypt at the behest of its British advisors. Khartoum fell to the Mahdist forces in January 1885, solidifying their control over Sudan and entrenching it with their brand of Islamist ideology. Muhammad Ahmad died in June 1885, but the identity of his successor was hotly contested among three claimants. Nevertheless, after putting down internal revolts over his legitimacy, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad was ultimately deemed to be the successor-Caliph in 1891.

By the 1890s, the Egyptian financial system was successfully reformed, now being able to allocate resources to defeat the Mahdist state. They took up where it had left off in the Mahdist War. Italian losses at the Battle of Adwa in 1896 encouraged the Mahdist Caliph Abdallahi to attack Italian post at Kassala, which in turn the Italians requested British assistance for defense. The British intervened, and in 1899 the Mahdist regime was toppled. British intervention to bail out the Italians gave the British a legitimacy to overtly rule Egypt, especially to defend the Suez Canal and maintain stability in the area of the Red Sea, especially in the face of inter-imperialist competition over the region of that decade. Anglo-Egyptian Condominium was formed and Sudan was administered under its flag until 1956.

Considerable space here has been devoted to reviewing the history of Egypt-Sudan, a history that is linked by the Nile River and the Red Sea region. What does all this have to do with the current Islamicized Sudan? It shows that the history and events in Sudan is inseparably intertwined with geopolitical events of the larger MENA region and states involved. And this not only is apparent in conflicts over plots of land. It manifests itself also in conflicts over ideas. This leads us to rise of a certain manifestation of political, fundamentalist Islam to which we will turn next.