In the midst of rising tariffs and economic uncertainty, a chord of relief was struck when on December 2nd, President Donald Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced a much-needed truce in their emerging trade war. Needless to say, businesses on both sides of the Pacific breathed a sigh of relief in mere hours. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index climbed 2.5% and the Shanghai Composite index jumped 2.6%. Japan’s Nikkei 225 index rose 1%. In the West, the UK’s FTSE 100 index, the CAC40 in France, and Germany’s DAX were all up by about 2% at the end of the day.

But a truce isn’t peace, and that has been reflected by the political maneuvering in both Washington and Beijing as the two governments prepare for the next round of trade negotiations. Which begs the question: What’s going on?

While this temporary armistice may have been struck in Buenos Aires during the G20 Summit, the origins of the US-China trade war goes way back to predate Trump’s populism or Xi’s imperial governance.

Trade relations with China, as well as many other Asian nations, for America, has always had more than just pure capitalistic benefit at heart. After all, it wasn’t until 1979 that the United States even established ‘normal’ economic ties with the Chinese. Up until Richard Nixon’s attempts to thaw relations during the Vietnam war, and President Deng Xiaoping’s liberalization of economic policy, the U.S. position on China had remained the same: passive containment. But it lacked heart, particularly in the face of greater foes such as the Soviet Union. In some cases, like with the Nixon Administration, Washington even viewed China’s contentious relationship with Moscow as potential shrapnel to be logged against the Kremlin.

In fact, the average American had a rather positive view of China as a result. In 1979, Gallup polling showed China’s favorability rating in the U.S. was 64%. In fact, up until the early 90s, China remained relatively popular, peaking at 72%. Even in the past five years, Uncle Sam’s Pacific neighbor has hovered in the 45% approval range back home.

Hoping to avoid conflict while still spreading Western concepts of economics and governance, much of America’s reasoning for a purposefully lax trade policy with China was the hopes that the connection would lead Beijing into the 21st Century as, at the very least, a neutralized threat. And to an extent, it worked. In 2001, the United States even backed China’s entrance into the WTO. But perhaps in an ironic twist to the US foreign policy of self-preservation and human rights, these initiatives designed to push China toward a freer market worked a little too well.

There’s even a term for it: Red Capitalism, which also happens to be a book written by Fraser J. T. Howie, a researcher who’s conducted extensive studies on China’s maneuvering in international markets. When asked about the recent truce, Howie told the Washington Post in an email “Markets should be happy, in that the worst is postponed. But I don’t see the West ever going back to business as usual with China. Too many genies have been let out of bottles.”

China took advantage of the open-door policy given to them by the United States in trade and used it to their advantage. Trade between the two nations reached $211.6 billion in 2005, compared to the $2.4 billion exchanged in 1979. From 2001-2005, the volume of US-China trade increased an average of 27.4 percent a year. As a result, the United States has become the top market for Chinese merchandise and China is buying up more U.S. goods, with U.S. exports to China rising 21.5 percent in each of the last four years.

But China hasn’t been the only one utilizing these open markets. By 2030, it’s expected that US exports to China alone will be a staggering $520 billion, according to a report from the US-China Business Council. To put that into perspective, the combined trade between Beijing and Washington in 2017 was worth $710 billion dollars. The United States has continuously operated as a high-value trade partner for the Chinese, providing trucks and construction equipment, which totaled profits of $6.7 billion in 2014 and $7.1 billion in 2015. US exports to China made 1.8 million new jobs and $165 billion in GDP in 2015 according to the same report.

Overall, while cheaper Chinese products have created a damaging trade deficit and led to the dissolution of countless U.S. jobs over the years, it’s also necessary to note that this imbalance hasn’t been without its positive effects. It’s estimated by the US-China Business Council that the flood of cheaper products have lowered overall prices in the marketplace by around 1.5%, which when taking into consideration that the average family in the states made $56,500 a year in 2015, means that this trade balance saved these families around $850 a year.

The reasons behind this trade deficit of $335.4 billion are rather straightforward and simple: American businesses’ reliance on cheaper Chinese products have led to the U.S. importing more than it exports to Beijing.

Many argue that the main reason for the economic imbalance between these two superpowers – China’s overall cheaper pricing – is purely an artificial ploy by the government. By devaluing the yaun, China’s currency, at a rate of 40%, Beijing has kept it below free-market levels. While China did agree in 2005 to a 2.1% increase in the yaun’s value, it pales in comparison to the work needed to restore the currency to normal levels, a claim backed up by the director of the Institute for International Economics, C. Fred Bergsten, among others.

Strangely enough, unlike the vast majority of issues that face the United States, the problem of trade with China is a matter that draws bipartisan support. A recent UBS poll shows that 71% of U.S. business owners want a tariff increase on Chinese products, a belief shared by 59% of high-value investors in the same survey. Even politicians seem to agree on the issue for the most part.

“China’s refusal to play by international economic rules cripples our ability to compete on a level playing field.” Sen. Chuck Schumer, current Senate Minority Leader said back in 2006. Republican Lindsey Graham (R-SC) sponsored a bill in that year that would have levied a 27.5 percent tariff on all Chinese imports unless the yuan was significantly revalued. However, the bill never made it to President Bush’s desk, as it was withdrawn in March after the two lawmakers visited Beijing.

President Trump’s surprise victory in November of 2016 shook the dynamic of this decades-old relationship to its core. His populistic rhetoric and his position as the US champion of protectionism made some think that as a man, as an idea, he was unelectable. But Donald Trump didn’t invent the concept of ‘America First’ all by himself; he carefully utilized the seed of discontent that had been sowed years ago. His talk on China had always been tough, a mirrored reflection of much of his positions in general on the campaign trail.

“China is neither an ally or a friend — they want to beat us and own our country” – a tweet from Trump on Sept. 21, 2011.

“We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country and that’s what they’re doing. It’s the greatest theft in the history of the world.” – another from the campaign trail in May 2, 2016.

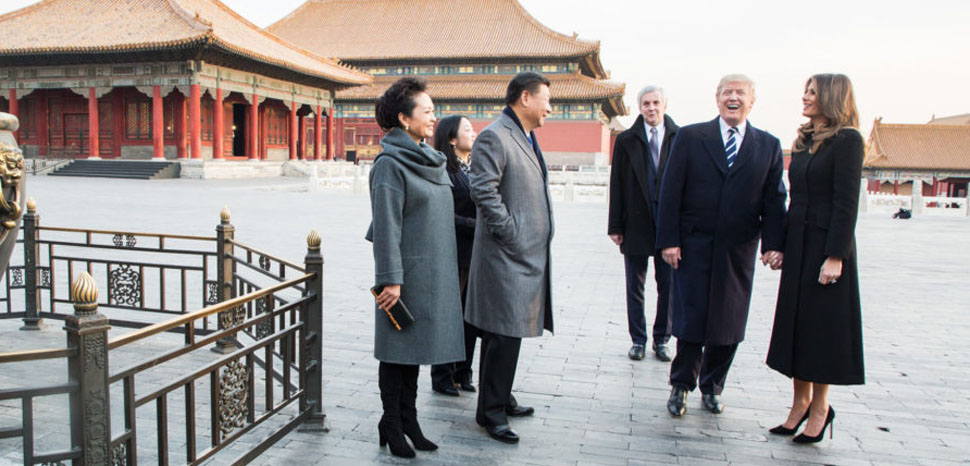

But when Trump made his first visit to the Chinese mainland early in his term, hints at a more moderate tone seemed to emerge. “I don’t blame China,” Trump said in Beijing. “After all, who can blame a country for being able to take advantage of another country to the benefit of its citizens?” But then, for a while, it seemed like maybe the 2016 candidate was back in the saddle.

Tariffs on products worth around $250 billion were levied on Chinese products by the Trump administration in 2018, with Beijing responding with tariffs of its own. But the G20 Summit resulted in some concrete results, with the Chinese Foreign Ministry confirming that the two leaders had instructed their teams to intensify talks. A truce in economic hostilities was also announced, a period to be accompanied by talks that should last around 90 days. A 40% decrease in Chinese tariffs on U.S. cars is also rumored to be in the works.

Yet some analysts argue that the issues go far deeper than just a trade deficit. Barclay’s Ajay Rajadhyaksha told CNBC in October at the Barclays Asia Forum in Singapore: “This is not the U.S. and NAFTA. This is not the U.S. and the European Union … There is a significant part of the US administration that is worried about China’s technology ambitions. The administration wants fundamental changes in how the Chinese treat intellectual property, how they talk to technology companies looking to invest in China. This is not about the trade deficit. If it was, it would be easy to solve.”

Saying that it’s almost impossible to come to any truly comprehensive conclusion on the full impact of the world’s most powerful trade relationship is an understatement, but it’s not hard to see that things have changed, and probably permanently. “Business as usual” isn’t a term we can accurately use anymore when talking about these two giants of the Pacific. The partisanship may continue, as well as the political hearsay, but the facts remain the same. A lot rides on the coming talks, and the impact they will have on the global economy is unpredictable.

I guess you could say: “it’s complicated.”

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect the official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any other institution.