Personal Leadership and Systemic Constraints

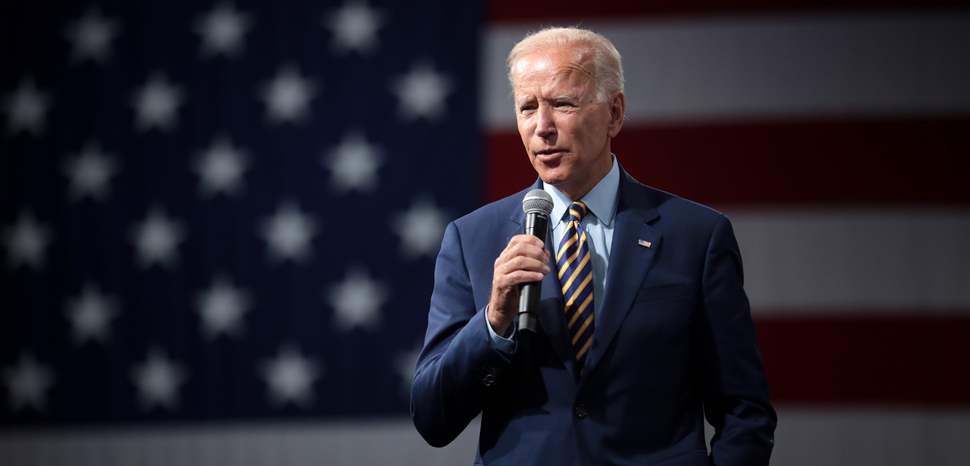

President Trump’s leadership style has been a highly controversial topic and opponents have been pointing to his often unorganized and impulsive approach to international affairs. Though the enthusiasm for his upcoming competitor, former vice president Biden, seems to be rather low at this point, many feel much more comfortable with his approach to political leadership, which has been on display for several decades.

Even if such criticism is justified, we should ask the question of how far does political leadership really go within the international arena? This is a contested topic on its own but even those who see the strategic orientation of a country as the product of systemic features of the international system, usually acknowledge that the personal style and agenda of leaders are at least influential in the short term.

Though realists tend to focus on the structure of the international system, they do not necessarily diminish the importance of political leadership. They rather interpret the role of a leader as an administrator of the state on the way to a preset strategic end-goal. Like a pilot in a modern airplane, the leader’s task at hand is to ensure that his state arrives at its set destination safely and in due time. Like the plane, the state is on autopilot most of the time, but it is the leader’s job to recognize irregularities as well as technical issues and to deal with them accordingly.

Therefore, the critics point is fair – bad leadership can indeed be very dangerous. Anyone who can imagine being on an airplane, where the pilot spontaneously decides to fly an air-show maneuver, might get an idea of how some foreign policy professionals felt since the current president has been inaugurated.

While “impulsive and unorganized” might be one style of bad leadership, it is not the only one. Another main issue of lackluster leadership is the misperception of where the strategic destination lies. To come back to the airplane analogy, I recently read a story about a pilot who was supposed to fly from London to Duesseldorf but flew to Scotland instead. As in air travel, getting the actual destination wrong is a rare occurrence in the field of foreign policy making. Delayed take-offs and turbulent landings are more common occurrences. Similarly, political leadership often delays grand strategic adaptations or wastes crucial resources on non-vital issues or lost causes. Those failures are eventually corrected by systemic pressures, though damage might already be done, and important windows of opportunity will pass.

Biden’s Views on NATO – Is “Return to Normalcy” a Strategy or just Nostalgia?

This brings us to Joe Biden’s foreign policy pitch. Trump’s critics claim that his leadership results in unnecessary risks and squandered opportunities due to a lack of a comprehensive strategy. Biden, they argue, would bring a “return to normalcy” and a more professional conduct of foreign policy.

In his essay in Foreign Affairs and his speech in July 2019, Biden lays out three core strategic goals – American prosperity, security and the promotion of democratic values. He also claims that every US president has pursued these goals except for Donald Trump. Accordingly, he sets forth to propose a reversal of the foreign policy course taken since 2017 and bring it back to the status quo ante (henceforth “return to normalcy”). This point is well received by those who criticize the blunt and often erratic leadership style of the president and wish for a foreign policy reset.

Particularly regarding NATO, many in the foreign policy community would like to see a full U-turn from Trump’s transactional high-pressure approach and find themselves relieved by Biden’s early focus on reinforcing the traditional alliance structure. Yet, this view ignores structural developments in the international system that make a simple return to the old counterproductive.

NATO’s struggles are not new. The current administration only put them into the center of attention. The organization was created as an alliance of democracies with the goal of containing communist expansion into Western Europe. During the Cold War, the alliance was therefore a logical product of shared values as well as shared strategic interests, as the Soviet Union has clearly been an existential threat to all members.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the strategic ground suddenly disappeared, and NATO leaders set upon the task of finding new strategic meaning for the alliance. Neither the debates over moral guidelines of R2P concepts – nor the Global War on Terror- nor a renewed Russian threat to NATO’s eastern flank filled this strategic void. To many member states, none of those humanitarian and security threats were existential in nature. All those themes failed to result in cohesion and reliable commitment to the alliance that has existed during the Cold War.

Consequently, political leaders attempted to give NATO meaning by reinforcing the narrative of an “alliance of democracies” and started to use the organization as a proxy for the transatlantic relationship at large. Biden seems to follow this rhetoric repeatedly underlining the importance of NATO as the central pillar for democratic alliances in the world, which he seems set on revitalizing. I would argue this is an overly broad and unnecessary approach to military commitments. Instead of taking an aged military alliance that has been hollowed out of its original purpose as a proxy for the transatlantic partnerships, we should rethink existing alliance structures at their core.

Through its immense power and default geographic positioning, the US had the luxury of pursuing an ill-defined foreign policy since Washington’s last peer competitor bit the dust in 1989. This is changing now, and at an accelerating speed none the less. As has been outlined by the Trump administration in the 2017 National Security Strategy, the US will be refocusing on the containment of “revisionist” great powers, particularly Russia and China. Many nations of NATO’s former Cold War core do not prioritize the goal of containment.

Germany, the most prominent example of the Trump administration’s quarrels with the alliance, is one of those countries. Berlin likes to see itself as a Zivilmacht (civil power), a concept summarized by Hans Maull in 2007. This concept fits well with the country’s historically found reluctance of using military forces as a strategic instrument – or to even build operational military forces. Instead, Berlin prefers to utilize its economic and soft power to promote democratic values through multilateralism, and sees itself as a driving force on collective action problems, like climate change.

During the Cold War, Germany was able to sufficiently commit to NATO as the Soviet threat was existential and painfully visible in the division of the country along the Iron Curtain. The subsequent success of the alliance was the very factor that contributed to Germany’s unwillingness to meaningfully contribute. The end of the Cold War brought unification and relative security; Berlin’s outlook on NATO drastically changed and the country’s political elites were eager to reap the so-called “peace dividends” by continuously shrinking their defense budget. Furthermore, Berlin is generally softer on Russia and tries to establish closer energy relations with Moscow, to the anger of their partners in Washington.

Germany is only the most prominent example for this. Freeriding and a lack of a shared strategic vision became an issue between the US and many other European NATO member states. In 2019, only nine of its 30 member states met the NATO guideline of spending 2% of their GDP on defense. Additionally, France and Italy, two other major European powers, also seek more cordial relations with Moscow than the US would like to see.

NATO’s new members – Poland, Romania and the Baltic states on the other hand – have been willing to closely cooperate with the US and follow Washington’s lead. Moscow’s proven willingness to leverage military force to achieve its goals, is still an existential threat to these countries. While it might be viewed as an ugly violation of international law in Berlin or Paris, Russia’s military adventures are downright frightening to the governments in Warsaw and Tallinn.

Though the president’s rhetoric on NATO is controversial and might damage the trust between Washington and certain US allies, his actions lead in the right direction. In an international system drifting toward greater multipolarity, Washington should follow the saying of Frederick the Great: “He who defends everything, defends nothing.” President Trump’s initiative to shift the new military focal point from military bases in Germany to Poland is an important first step toward a functioning containment-alliance in the “Intermarium.”

This is not an excuse for inept leadership on the matter. As I mentioned, the president’s approach to America’s NATO allies is too confrontational. In order to rethink the transatlantic partnership, US interests should not be reduced to a transactional relationship limited to economic and military cooperation. Western European partners, like Germany, are important and they are necessary to support Washington’s leadership role on the global stage. Alliances are indeed multi-dimensional, but the US should attempt to disentangle its main military commitments to allow for a shared strategic ground between vital military allies.

US presidents should start to fundamentally rethink military commitments and alliances in Europe instead of pushing a “return to normalcy” narrative. It is not 1985; the global context has changed and so should the alliance structure.

Those who hang on to NATO often do so for nostalgic reasons. Most of their worries are unfounded. For example, the disappearance of NATO would not mean an end to the US-German partnership. It would arguable improve it at this point in time. Avoiding endless debates on burden-sharing between NATO’s main security guarantor and a self-described “civil power” would allow for closer cooperating on common non-military interests on the global stage.

Other traditional partners might still share military interests. Yet, the most important ones do not even relate to the framework of NATO. France has arguably the most comprehensive grand strategy of all major European countries and is the best positioned European player in Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of military ties and strategic vision. The UK enjoys its “special relationship” with the United States and both nations cooperate closely in several theatres. Yet, those partnerships are mostly realized on a bilateral basis and they precede NATO. Therefore, there is no reason to believe that military cooperation between such traditional partners with shared interests will not resume without NATO.

On the other hand, NATO’s consensus-based decision-making prevents the US to efficiently pursue its national interest, because of the impeding influence of the original NATO-rump that diverges from the strategic outlook that the US and its Eastern European allies share (see John Deni’s argument).

In the end, Biden might very well turn out to be the better foreign policy leader, combining a more professional style with cautious strategic adaptions to the fundamental changes in the international system. Nevertheless, he provided plenty of reasons to be concerned during his early campaigning efforts. Military alliances should not be established on a permanent basis. This confuses strategic means with strategic ends. The importance he attributes to NATO is not reflective of strategic realities anymore. If his stance is more than just comforting rhetoric for the swing-voter, who wishes Trump to simply go away, this is going to be a problem.

Indeed, being a foreign policy brute is a net negative and President Trump’s transactional and undiplomatic approach to NATO might damage the trust of US allies. Nevertheless, “return to normalcy” and “anything but Trump” are political slogans and not a functioning strategy. Causing damage due to a disruptive leadership style is one problem. Ignoring the changing strategic demands of the international system is another. Therefore, those who support Biden’s presidential run should put him under serious pressure on the matter, if they want him to be a president who sets the US on the right path. Should the “return to normalcy” become the leading foreign policy principle, the US will pay a high cost of opportunity as Washington delays necessary strategic adaptations.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the authors are associated.