Despite the Trump administration’s abrupt withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Hanoi wants Washington to know that it remains a viable economic and strategic partner and is poised to check the hegemonic influence of their longstanding rival China.

The agenda in the Trump-Xi meeting at Mar-a-Lago failed to address any of the intractable South China Sea issues, and US freedom of navigation operations near Chinese military outposts in the Spratlys seem to have dramatically fallen off the Pacific horizon. These geopolitical issues have left many wondering whether the upcoming visit of Vietnam Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc to Washington is a proactive step of Hanoi to boost cooperation and to deepen a partnership with the U.S., all in an effort to prevent Washington’s further retreat from its position in Asia.

Naturally, the Vietnam’s delegation has high hopes that it will gain some assurance that Trump will travel to Vietnam in November to attend the Asia Pacific Economic Conference. Meanwhile among several policy shapers in Hanoi’s Diplomatic Academy, there’s a feeling that Vietnam is a low priority for President Trump, who’s primary, if not only Asia focus remains China and the North Korean nuclear threat.

“They also want to get a reading on how the Trump administration plans to engage the region economically after the president canceled the TPP, in which Vietnam would have been a major beneficiary,” claims Murray Hiebert, a senior advisor and Southeast Asia director at the Center for Strategic International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C.

In an executive order in late April, Mr. Trump recast his campaign message to “Buy American, Hire American.” His patriotic refrain opposes free trade deals since he claims that they take away jobs from Americans. His strident language argues that he would protect American workers against competition from low-wage countries.

The US withdrawal creates a political and economic vacuum that China is more than eager to fill.

Consequently, he intends to “negotiate fair bilateral trade deals that bring jobs and industry back,” which allow the U.S. to quickly terminate the deals in 30 days “if somebody misbehaves.”

At times, Mr. Trump’s message appears straight out of his 2016 campaign playbook. His trade stance mirrors a growing feeling among many Americans that international trade deals have hurt the US job market. However, most consumers realize that price is the bottom line. Nevertheless, his executive order is directed to federal agencies that require them to buy American-made goods and to cut down on waivers and exemptions to those rules.

For now, the business community believes that the Trump administration is detached from the reality that goods are sold cheaper in the U.S. because they are made overseas; and that US companies also benefit from trade deals, making trillions of dollars selling their own products overseas.

Republican Senator John McCain has described US withdrawal as a “serious mistake that will have lasting consequences for America’s economy and our strategic position in the Asia-Pacific region.” He said the decision will “forfeit the opportunity to promote American exports, reduce trade barriers, open new markets, and protect American invention and innovation”

More significantly, it will “create an opening for China to rewrite the economic rules of the road at the expense of American workers.”

The US withdrawal creates a political and economic vacuum that China is more than eager to fill. Beijing has wasted little time in seizing the opportunity in the absence of clear Asia Pacific policies from Washington. Chinese Communist leaders have ramped up their globalization efforts and have championed the virtues of free trade. In an address to the World Economic Forum (WEF) at Davos at the start of the year, Chinese President Xi Jinping likened protectionism to “locking oneself in a dark room” and signaled that China would look to negotiate regional trade deals.

While Vietnam, a war-hardened nation, can’t choose its neighbors, it can certainly choose its friends. Once-implacable foes burdened by a bloody and tragic history, Washington and Hanoi increasingly share overlapping strategic interests that could redirect the trajectory of security cooperation in the contested South China Sea.

What’s clear is that the U.S. and Vietnam signed a Comprehensive Partnership in 2013, which covered trade, development, and maritime security but did not call for specific action. Vietnam has applauded the Trump administration’s strong language when the White House referred to “China’s military fortress” in the South China Sea. However, this rhetoric has quickly faded since the administration has called upon China to pressure North Korea to forego any further nuclear and missile tests.

“However, the US decision not to conduct more assertive freedom of navigation operational patrols (FONOPS) earlier this spring sent a clear message to ASEAN that they could not count on the U.S. to counter-balance China,” claims Professor Carlyle A. Thayer, director of Thayer Consultancy based in Australia.

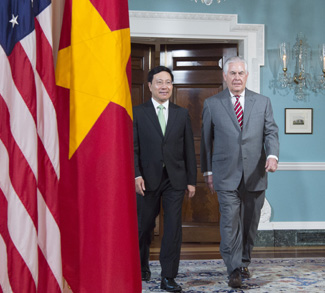

The ambivalent and inconsistent State Department Asia policy is reflected in the most recent rhetoric of U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who delivered an emphatic message last week to foreign ministers from Southeast Asian nations that militarization and construction in the South China Sea must stop while territorial disputes in the area are worked out.

Tillerson’s message – aimed at China, which has reclaimed thousands of acres of land in the South China Sea in recent years – underscored that Southeast Asia remains a very strategic partner for the U.S. on a host of issues, including trade and security cooperation. Vietnam makes no pretense that it wants the United States to continue to be its leading trading partner.

Two decades after trade normalization, the U.S. and Vietnam are now drawn closer together due to China’s economic and geopolitical rise. The withdrawal from TPP remains particularly disappointing on the trade front for Vietnam. It lacks a comparable bilateral free trade agreement with the U.S., since it’s their largest export market.

For the Vietnamese, their economic progress is uneven. Ho Chi Minh City alone accounts for 23% of national output and 24% of exports – far in excess of its 9% share of population. Nevertheless, Vietnam’s economic success has been accompanied by a dramatic reduction in poverty. Its $200 billion economy, almost 40 percent of which comes from manufacturing, has grown sharply since 2011, largely on foreign investment in the export of goods like smartphones.

Real GDP will grow by 6.2% in 2017 – the same rate as 2016. A significant pickup in exports (supported by depreciation of the dong) and strong growth in private final consumption are the main drivers. Vietnamese gains in manufacturing offset an unsteady performance in agriculture and this is especially evident in the Lower Mekong Delta.

According to market observers, Hanoi plans to introduce a number of market-friendly reforms to boost confidence in their economy.

Looking forward, the Trump administration’s focus on bilateral trade agreements with major trading partners provides little scope for engagement with Southeast Asia, or even the possibility of a re-packaging of the TPP.