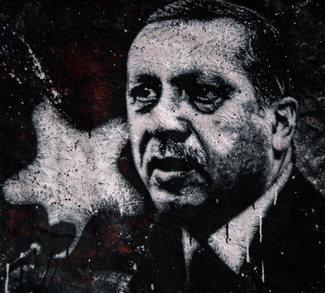

The recent rapprochement and normalising of relations between Ankara and Moscow was supposed to put to bed the difficulties and strains in the relationship after the November 2015 downing of a Russian Sukhoi Su-24M jet by a Turkish F-16. The recent coup attempt, the ever present ISIS attacks on Turkish soil, the impact of Syrian refugees and the ongoing difficulties with the Kurds, both PKK and YPG in Syria, had necessitated a recalibration.

The apology and placing of blame on the now Gulen-linked F-16 pilot was supposed to benefit both Russia and Turkey, allowing them to move forward. For Putin it was one less distraction and difficulty, better securing his navy’s position and its ability to enter and exit the Black Sea via the Bosporus Straits. Turkey would now have closer relations, having shifted somewhat from the US and NATO in response to their lukewarm support during the coup (and widespread belief that the U.S. at least had foreknowledge of the coup).

Erdogan’s St Petersburg visit would also bring news of the revival of the previously scrapped Turkish Stream project, bringing a direct gas pipeline from Russia’s Black Sea region via the Black Sea to Turkey before entering Greece. Both sides would benefit financially and guarantee the strategic development of economic and energy security. Moreover, the increase in the ultra-nationalist presence under the AKP umbrella and centres of power, particularly in the military, taking the spaces left behind by the purges of Gulenists is likely to lead to an increase in pro-Russian sentiment, while the anti-Kurd stance continues. The re-emergence of conservative and nationalist Kemalist elements is directly contrasted to the decline of Gulen loyalists. A greater degree of separation from Washington was, and to a degree still is, on the cards.

However, the news that Turkish tanks and Ankara backed rebel forces entered Jarablus in order to clear ISIS from the border region and claim land for the rebels is a net gain for Washington, as much as it is for Turkish objectives. If successful, the strategy will further protect the Turkish border, strengthen Ankara backed rebels in the war for Aleppo and reduces the chances of further ISIS attacks in Turkey.

An expansion in Turkey’s role in Syria, of course, increases the risk of direct conflict with Russia, likely through a repeat of the November 2015 scenario, but it also highlights the zero sum game that Ankara and Moscow are playing in Syria.

While the U.S. has generally utilized the Kurds as a regional agent, exploiting their aspirations vis-a-vis Kurdistan, their interests will be disregarded if they conflict with more important short and medium-term objectives.

While both now share similar objectives regarding ISIS, which explains the Lavrov — Kerry talks in Geneva and potential for agreement on the issue, their other objectives remain in juxtaposition. Turkey wishes to see the fall of Assad and control of Syria by a Sunni Muslim majority that will side with Turkey going forward. Russia uses its Syrian bombing campaign to prop up Assad in order to maintain its naval base at Tartus and guarantee Iran’s links and dependence on Russia. It would also like to avoid the U.S. and Turkey expanding their presence in the region, strengthening positions on Russia’s southern flank. The loss of Tartus would make Russia’s access to the Black Sea more precarious, reliant upon good relations with Turkey. Its boldest foreign policy steps from the Georgian war to the Ukrainian war and Crimean annexation have centred on the Black Sea. Russia’s recent naval expansion and control of Sevastopol has extended its power projection within the Black Sea, in direct opposition to the other major power: Turkey.

Of course, the key to the incursion are the Kurds. While Erdogan maintains and strengthens relations with the Iraqi Kurdish region, Turkey desperately wants to finish off the PKK and ensure an end to Turkish Kurd secessionist hopes. The success of the YPG in the Syrian conflict raises the possibility that a post-war autonomous Kurdish region within Syria could be established unilaterally or through negotiated settlement. Turkey would see such an outcome as an inevitable precursor to the formation of an independent Kurdistan. By driving ISIS out of the border region and forcing a Kurdish withdrawal east of the Euphrates Turkey would achieve its double objective of helping its Syrian rebel allies and stopping further Kurdish dominion over the border, thus securing its southern flank.

The fact that the Americans are providing air support and instructing the Kurds to fall back suggests they are attempting to mend relations with Ankara after the post-coup attempt recriminations and Turkey’s Russia recalibration. Turkey is unlikely to have entered Syria the way it did without significant planning and agreement from Washington.

The U.S. won’t extradite Fethullah Gulen, but they will use their influence over the Kurds to give Turkey a win. With a retreat of the YPG in Syria, in the medium term, Turkey would have more breathing room in southeast Turkey in its engagement with the PKK, even though PKK attacks in Turkey’s Kurdish regions will continue to increase in scope and intensity.

The move also indicates that Washington understands the importance of Syria and Turkey’s difficulties with the Kurds. While the U.S. has generally utilized the Kurds as a regional agent, exploiting their aspirations vis-a-vis Kurdistan, their interests will be disregarded if they conflict with more important short and medium-term objectives. The U.S. places more value in its relationship with Turkey than it does the Kurds.

In addition, the Americans are also attempting to undo the progress in the Russia-Turkey relationship after Erdogan’s St. Petersburg visit. The Turkish incursion heightens the tensions, guaranteeing a somewhat strained relationship between the two former imperial powers. In the short term, it keeps Turkey away from the Russian camp, unless the strategy involves Turkey siding with Assad’s forces to fight the Syrian Kurds.

However, the news that Turkish and rebel forces have engaged with the YPG and the Syrian Democratic Forces in Jarablus and Manbij, a town 38km further south, is not a positive development for Turkey or the situation as a whole.

While the U.S. will need to use its influence to ensure a Kurdish withdrawal if it wants to help Turkey, the longer this initial incursion lasts the more dangerous the potential blow-back for Ankara. The Kurds may decide to push forward with their objective of linking the Kurdish controlled zone east of the Euphrates to the isolated pocket in north-west Syria around Afrin. The Kurds may decide to call John Kerry’s bluff with regard to his threat of ending US support if they do not fall back. The United States still needs Kurdish forces in Syria.

There is also the possibility the 150 km distance between Manbij and Afrin is too much even for the SDF and YPG. At worst, fighting will continue either until Turkey expands its bombing campaign or until the United States applies enough pressure.

This development, combined with Iran’s withdrawal of Russia’s Hamadan airbase access, has the potential to increase tensions in Ukraine. While Putin would be unwilling to fight two wars simultaneously, he might consider a short term scale-back of operations in Syria so that Turkey can achieve its anti-Kurd objectives, combined with an escalation in Ukraine. John Kerry’s talks in Geneva with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and a potential cease fire indicates that both sides are aware of a potential escalation and are therefore attempting to reach a consensus to de-escalate and/or solidify positions. Such a move would reduce the risk of Russia coming into direct contact with the US and Turkey, while Putin could use his Ukraine strategy as a way of regaining the initiative in the run up to September’s Duma elections and the upcoming talks over Ukraine.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.