2017 has been an active year for health authorities in Africa, with the establishment of Africa’s own CDC in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and another regional prevention center opened in Abuja, Nigeria, post-Ebola efforts to prepare for the next major outbreak appear to be gaining momentum. However, these efforts lack the acknowledgment of sufficient conditions to keep pace with the manifold threats in the areas of health and human security in Africa. With the prevalence of infectious diseases across the continent and numerous fragile health systems, government authorities and cross-national agencies throughout Africa are alarmingly unprepared for increasingly important issues in health and human security combined.

International health security is becoming increasingly linked to human security. While there remains no consensus on the definition of health security, the concept has developed over many years and now encompasses a wide array of conceptual and substantive challenges. To date, multilateral organizations like the United Nations (UN), World Health Organization (WHO), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), National Institutes of Health (NIH), European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC), the European Union (EU), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), among others, have made great strides in building a common health security language. Identifying areas of common concern has been valuable for recognizing issues of significance shared by multiple communities and states, and building on that shared language.

Recently appointed Scientific Director of the Canadian Institute of Population and Public Health (CIHR), Dr. Steven J. Hoffman, has contributed to a public understanding about the intersection of health security and human security. In doing so, he has drawn attention to the term “global health security,” which he notes, “focus[es] on protecting entire populations, rather than individuals, from threats of global proportion that can spread menacingly irrespective of established natural or political borders.”

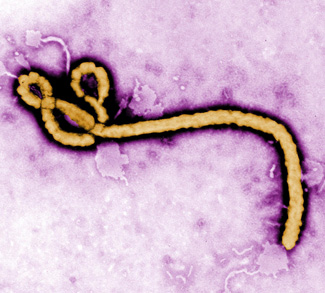

Approximately a year ago, the WHO officially terminated the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) for the 2014 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak. The epidemic affected multiple countries in West Africa and was the most extensive EVD outbreak ever recorded. The WHO’s efforts, in combination with other national and supranational entities, in part, were not orchestrated with the concept of global health security in mind.

The WHO’s senior officials were open about their poor response, together with international partners, immediately after the EVD epidemic. They claimed to have been “ill-prepared” to contain the spread and handle the manifold impacts of the disease that presented global policymakers and respondents with overwhelming implications. Some health experts denied the possibility of Ebola Virus Disease outbreaks and spread on the scale that was seen back in 2014. The EVD outbreak underpinned the reality of the WHO’s relatively limited capacity and operational reach during such a health crisis, and offered some insight into funding implications, and how some diseases and regions can be prioritized over others. Moreover, it signals a need to rethink appropriate strategies in preventing the next wave of outbreaks: Populate the world with new centers, or strengthen the existing system and focus on conditions necessary for healthy and robust communities?

As was the case with the West Nile Virus (WNV) in 1999, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, H1N1 in 2009, and MERS-CoV in 2012, Ebola put the spotlight directly on highly infectious diseases’ ability to outpace health professionals’ response capacities, including organization, management, and containment. In the aftermath of these experiences, the WHO also received a cornucopia of criticism for not drawing on important lessons that could aid in future outbreaks.

In April 2015, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan, Deputy Director-General Anarfi Asamoa-Baah and the organization’s regional directors admitted, “[w]e can mount a highly effective response to small and medium-sized outbreaks, but when faced with an emergency of this scale, our current systems – national and international – simply have not coped.”

The WHO’s April 2015 situation report depicted the virulence of EVD transmission that led to more than 11,300 deaths and 28,500 infections, highlighting the need for “adequate levels of preparation in tandem with ‘rapid and adequate response.’” While identified as part of the requisite conditions for successful preparedness, they cannot be so easily identified in post-EVD regions or other areas that remain susceptible to infectious diseases and rapid spread.

Since the EVD spread, “highest priority” countries – Ivory Coast, Guinea Bissau, Mali, and Senegal identified as being at highest risk – followed by “high priority” countries – Burkina Faso, Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, South Sudan, and Togo –have received insufficient attention by the WHO as well as international and local partners in preparing for future encounters.

Some standard viral hemorrhagic fever Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) modules were distributed to countries where excessive measures were required the most, but those modules were shown to contain inadequate materials to fulfill protection needs, and to ensure essential and lasting counter-disease functions and operations. Although “priority countries” have received technical support through the presence of some Preparedness-Strengthening Teams (PSTs), and assessment activities have been undertaken in different countries and regions, these and other combined efforts can be characterized as responsive rather than preventative. Can 90-day plans organized in each country protect communities across multiple national border against epidemics that can spread aggressively over a period of several years or more?

The WHO’s 2016 Zika declaration, which called the epidemic a global health emergency, revealed the passivity of the organization – in addition to loosely interconnected health systems and structures – that struggled to mobilize an effective response to a virus that many, even after becoming infected, had never heard of. In the case of Zika, the virus spread to nearly every country in the Western hemisphere, coming dangerously close to continental Africa, and led to the mobilization of leading scientists and health experts at all government levels.

The Africa CDC symbolizes a step forward in building and subsequently developing Africa’s communicable disease response.

Officials were perplexed by questions about transmission, birth defects, prevention, and future implications during the course of Zika’s assertive spread. Other than having declared a global emergency, the WHO received waves of criticism for its lack of action, delayed action, and its ineffectiveness. The crisis led to panic, and governments turning to forced abortions and sterilization as nefarious human rights violations aimed at suppressing the virus. It was an epic example of how the crisis of pandemic can be distorted and how the issue of health can be (over) securitized. Sexual transmission received relatively little attention by most governments, while the mosquito narrative received excessive coverage. The Zika epidemic also exemplified how governments remain not only predominantly ineffective at mosquito control, but also at managing the transmission of diseases through sexual contact – a necessary component of education programs in every country.

Zika further proved the willingness of governments to test new technologies, and experiment with potentially preventative measures, some of which conflict with individuals’ right to life and sovereignty over their bodies. The virus underscored the question of genetic experimentation, with the introduction of male mosquitos containing altered genes leading to a shorter life span. Female mosquitos carrying bacteria inhibiting their capacity to transmit viruses and disease were also released.

Jeff Bessen at Harvard University noted that genetically modified organisms (GMOs) may be a valuable ally in the fight against deadly viruses. “Perhaps the most dramatic example of GMO use in medicine,” he writes, “came during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. When American doctor Kent Brantly and other Western volunteers contracted Ebola, several were cured by a ‘secret serum’ called Zmapp. Manufactured by genetically modified tobacco plants, it’s a mixture of several proteins that attack the Ebola virus.”

In the aftermath of the Zika crisis, important questions about its origin, transmission, and effects have gone unanswered. The pitch of Zika revealed major fractures in scientific cooperation and possibly a dangerous disconnect between the scientific community and governments willing to enact strict, even if blatantly ineffective, measures to combat the disease. Failures to produce vital data on the Zika spread translates into little knowledge about who, if anyone, is immune to it or how many people would be vulnerable if or when Zika were to return.

If Zika were to reappear, this time in Africa, EVD and experiences with previous infectious diseases there could provide a look into the negative impacts that extensive transmission would have. Sexual transmission has been repeatedly downplayed as a mode of transmission. Previous experience showed that travel alerts, such as those made by the CDC and inspections at border crossings produced little in the way of containment.

Central and South America’s recent experience with Zika should have raised more questions about the level of preparedness for Africa’s imaginable encounter with the disease. The latest Ebola ordeal offers a glimpse into the problems of containing a disease with mysterious characteristics. Coupled with a lack or supplies stockpiled, lack of necessary funds and funding, and lack of health and scientific research institutes, the EVD and Zika cases foretell further health crisis for the continent, particularly given the fragility of existing health systems and the level of attention individuals in the most vulnerable parts of Africa give to their personal health.

Laboratory testing and diagnostics in Africa can be identified as one of the deepest problems in combating future disease. Some experts have noted a dearth of laboratory testing in areas deemed critical. Another problem stems from the absence of localized efforts to test for and maybe treat diseases – anything from Ebola to Zika. The United States’ (US) CDC, the United Kingdom’s (UK) Public Health England’s Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory (RIPL), and South Africa’s National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) provide a view to the type of operational capabilities needed in other countries. Having identified “priority countries” in Africa, the WHO is in a position to make recommendations and support similar operations in those areas. The African Center of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID) at Redeemers University, Nigeria and the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) are two cases of how similar initiatives are possible on locales susceptible to viral outbreak and spread, but they suffer from resource and staff shortages just as centers and institutes in the West do.

Part of building the necessary infrastructure that leads to strengthened preparedness entails increasing accessibility to vulnerable regions, yet with increased accessibility and openness comes the potential for increase spread. Effective management after an outbreak also means that government and health officials need to be proactive and ready to act. West Africa’s Ebola scare showed the need for more health experts ready and willing to work with national and international partners. EVD exemplified the willingness of local actor collaboration, with several governments having mobilized and deployed teams to contain EVD outbreak. Thus, the EVD experience demonstrated that essential human resources existed to build vital containment teams. The question is whether an increased number of teams would be equipped with the experts they would need and how long their resources would carry them.

Part of Africa’s vulnerability has stemmed from the absence of a unified body of health experts able to respond if and when needed. In the past several years, calls have been made for a center in Africa that reflects the operational abilities of the CDC in Atlanta. Its presence in Africa is expected to help close the gap between outbreak areas and response and coordination centers. In early 2017, the Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) was officially launched – backed by financing from the African Union (AU) – and includes the presence of every African country. Health authorities in other countries have built on the initiative with the establishment of regional CDCs such as that established in Abuja, Nigeria.

The Africa CDC symbolizes a step forward in building and subsequently developing Africa’s communicable disease response. Although, while Africa CDC’s main objectives include prevention, detection, and response to public health threats, its capabilities in these areas have yet to be truly tested. The Africa CDC aims to have centers across the continent, collaborating with both public and private agencies. Its initial goals have been set exceedingly high with its desire to provide universal vaccines by 2020. Given existing regional centers’ inefficiency in collaborating and coordinating among human and health security agents, the Africa CDC delivering on its goals remains questionable.

Former AU Commission Chair, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, who was succeeded by Chad’s Moussa Faki Mahamat, called it a “historic pledge” and claimed that it was an achievable goal. Currently only about a dozen African countries exceed the 50% mark of their national immunization programs, which has exacerbated Africa’s vaccine deficit – one out of every five children go without basic vaccines necessary for healthy living. Very weak levels of local pharmaceutical production leave health professional and task force under-equipped to contain complex outbreaks

Professor Jeremy Farrar, Director of the Wellcome Trust, recently opined that, “epidemic and pandemic diseases are among the greatest of all threats to human health and security, against which we have for too long done too little to prepare.” Human populations are surrounded by “natural reservoirs” of EVD and Marburg, for example, with fruit bats and insectivorous bats having been identified as the source of human health threats.

Given Africa’s increasing interconnectedness as well as the range of Africa’s delicate health communities, public awareness and local or community endeavors become even more important components in prevention programs. Literacy rates in those parts of Africa hit hardest by EVD between 2014 and 2016 were partly attributed to the “rumor mill” that emerged shortly after the outbreak with home remedies, including hot drinks and some raw vegetables, even Homeopathy being identified as dependable measures that would prevent the acquisition of EVD.

Much of the 2014 Ebola spread was attributed to the slow response of health experts in the field. Georgetown University’s health law professor, Lawrence Gostin, noted that, “Ebola is a very preventable disease,” and despite having over 20 previous EVD outbreaks, he said, “we managed to contain all of them.” The WHO’s slow response was also attributed to staffing and resource shortages, which raises questions about the potential for similar shortcomings to affect mobilization and response times by Africa’s CDC.

The creation and subsequent expansion of laboratories, based on the bio-medical approach of epidemics, is not be sufficient in responding to the prevention and management of future threats to health security. Epidemics are also determined by social, political, economic as well as cultural conditions to which the CDC unable provide total, complete, and effective responses. Existing emergency response centers and other facilities already fail to take the full spectrum of conditions into account when articulating the necessity to respond and prevent outbreaks.

Combating the next round of infectious diseases in Africa, and elsewhere, does not lie in the establishment of new centers and new institutions, but rather in mending the structural deficiencies inherent in the existing system. Building laboratories and specific centers for epidemics is only a partial and limited response to future threats to global health security. The activities of health systems are a small part of the response to future epidemics because the causes of the epidemics lie outside of the health systems (armed conflicts, exploitation of forest or mining resources, poor governance, state failure, and general insecurity).

If and when strengthened, programs within the existing system could be connected with broader and overarching initiatives developed at the Africa CDC. In light of recent experiences with Ebola and Zika, there remains much concern about how Africa’s new CDC and African nations will respond to the next major and unknown epidemic(s).