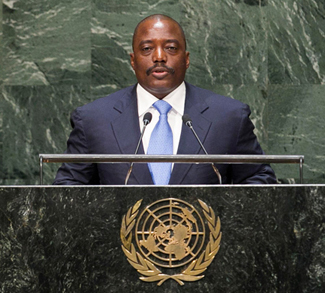

Congolese President Joseph Kabila appeared to be in his element while attending the 29th biannual African Union (AU) Summit in Addis Ababa this week, despite the fact that only days previously, he had begged off sick rather than deliver a speech at Independence Day celebrations. No doubt he was frightened that he’d be met with protests rather than adulations by appearing in front of a crowd after having broken his constitutionally mandated term limits. But surrounded by fellow heads of state in Addis, Kabila seemed blissfully unaware of the political crisis back home, arrogantly exploiting the summit as a platform from which to lobby his neighbors for support in reversing sanctions slapped on members of his government by the US and the European Union.

Unfortunately for the Congolese people, Kabila found a receptive audience. The AU Commission ultimately failed to address his refusal to relinquish power, only mustering enough courage to say it was “concerned about the political situation in some African countries, including the DRC.”

In addition to fueling violence within its own borders as a way to stave off elections, the government has also been employing subtler, more underhanded tactics to draw in allies.

Such failure to call out Kabila is far from isolated. Only last month, the beleaguered president received a significant boost in the shape of a state visit to South Africa – a visit that was also marked by the utter spinelessness of his hosts. During a reception in Pretoria, President Jacob Zuma not only declined to address his guest’s disdain for the democratic process, but also managed to praise Kabila for what he described as “progress” made in the DRC under his leadership.

Yet such silence on the part of Africa’s most influential heads of state and institutions could not come at a worse time for the Congo. At this point, it’s almost the last chance to convince Kabila to hold elections and to allow the return of country’s main opposition candidate, Moïse Katumbi.

Kabila was due to leave office in December last year, after having served the maximum two terms permitted by the country’s constitution. In an agreement sealed on December 31st, the government and opposition parties agreed that Kabila would step down and hold elections before the end of 2017. But so far, there is no timetable for his departure or for the next round of elections. Instead, all signs suggest that Kabila is engaging in what the Congolese call gliding – trying to delay elections until he can engage in the time-worn tradition of achieving a “constitutional coup” or installing a compliant political ally. In a rare interview with Der Spiegel, Kabila went so far as to deny that he ever promised to hold elections.

Not surprisingly, Kabila’s refusal to budge has fueled further turmoil in the already unstable country. As many as 20 people died in protests after Kabila’s second presidential term expired in December. According to the latest report from the Congo’s Catholic Church, more than 3,000 people have been killed in violent clashes between members of the security forces and armed militias in the central Kasai region since last August. The UN estimates that roughly 1.7 million Congolese have been affected by the violence and that 200,000 have been internally displaced. Some observers say that the government has been ignoring – possibly even stoking – violence in the region, long an opposition stronghold, in part to bolster its own argument that the country is unprepared to hold elections.

In addition to fueling violence within its own borders as a way to stave off elections, the government has also been employing subtler, more underhanded tactics to draw in allies. Last week, lobbyists working for the DRC organized a dinner with Congolese officials and Washington insiders at the Capitol Hill Club. The event was part of a whopping $5.6 million lobbying contract signed with multiple PR firms to gain support among US policymakers.

But the most critical component of Kabila’s strategy to stay in power is his quarantine of the only viable opposition candidate, Moïse Katumbi. The popular former governor of Katanga province left the country to receive medical treatment in May 2016 shortly after being accused on false charges of hiring mercenaries. Shortly thereafter, he was convicted in absentia of illegally selling a house that he did not own and sentenced to three years in prison. It didn’t seem to matter that the judge in that case later admitted she had been pressured to convict him and later fled the country herself.

It was all part of the president’s continued smear campaign against what he sees as his greatest threat. Following the death of longtime opposition figure Etienne Tshisekedi in February, Moïse Katumbi emerged as the only credible alternative to Kabila. The fact that, according to polls, the former governor comes out 18 points ahead of Kabila shows that the Congolese are largely unfazed by the accusations leveled by the regime. Knowing the odds are stacked up against him, it’s no wonder Kabila refuses to hold elections.

Which makes the silence of the AU and of regional powerhouses like South Africa all the more deafening. Neither country called on Kabila to allow the safe return of Katumbi, who is living in exile in Belgium. The sole exception is neighboring Angola, which has grown weary of the Kasai conflict, which risks spilling over the border. As African leaders dither, they would do well to remember that Congo has a long pattern of political, ethnic- and resource-based conflicts that have sucked in fighters from numerous African nations in decades past. They should make every effort to ensure this history isn’t repeated.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.