It is Nowruz, Persian New Year, this weekend and Iran would love to reach an accord over its nuclear program with the West, represented by the so-called P5+1 group, including the United States, the UK, Germany, Russia, and France. Tehran’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Javad Zarif after meeting US Secretary of State John Kerry in Geneva offered the optimistic prediction that the accord is “90 percent done.” Stranger things have happened. US companies encouraged President G.W. Bush to lift sanctions on Libya in order to allow the return of US oil companies to that country. The bombing of Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland in December 1988 was just one of the obstacles that had to be overcome. And, in that case as well, a renunciation of military nuclear ambitions was required. President Obama started the year by lifting the embargo against Cuba, facing similar congressional resistance, and propped up by relevant lobby groups in a combination that seemed unbreakable.

Iran’s potential return on the world scene without political constraints and sanctions would prompt a shift in the balance of power of the Muslim world. Tehran is the heart of the Shiite Crescent, which has engaged for decades in a religious, ideological, and military confrontation with the Sunni world represented most ideologically by Saudi Arabia, a formidable rival, which may prove as hostile as Israel itself. But Iran is useful to the West and to the region because it is a natural ally in addressing the threat from the Islamic State both in Iraq, where Tehran serves as a political pillar for the Shiite government in Baghdad, and in Syria, whose government Tehran has backed since the early days of the 1979 Revolution.

The negotiations of the next few days through March 31 have the potential to deliver a framework agreement. Complex points remain, but just as Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei and the White House are resolute about getting a deal, the Republican-dominated Congress is casting an ever longer shadow over its prospects of fulfillment. In recent years, attempts at a deal were blocked by both American and Iranian conservative forces, the latter headed by Ayatollah Khamenei himself, who has now succumbed to the idea that the Islamic Republic will have a better chance to prosper in a climate of relative peace with the West. Nevertheless, the letter sent by 50 Republican senators, who have threatened to annul any agreement between the presidency of the United States and Iran at the end of Obama’s term in office, will interfere with the negotiations in Lausanne. The White House, in turn, will have to reiterate to the Iranians and the American people that the president will veto any law proposed by a Republican majority in Congress, allowing for a 60-day period with which to review and potentially reject the agreement, effectively limiting the president’s ability to negotiate.

As if Israel was not enough; regional pressure is also coming from Saudi Arabia as Prince Turki al Faisal, former head of intelligence, in an interview with the BBC warned that should anything materialize from this weekend’s negotiations, his Kingdom would demand the same. The Prince hints that should Iran be left with the capacity to enrich uranium at any level, the Kingdom would demand a similar right – triggering a nuclear arms race in the Persian Gulf. Iran, however, seems less concerned about enriching uranium than lifting sanctions so that the country itself can enjoy some ‘enrichment.’ The Iranian Parliament in Tehran, the Majlis, in fact has demanded that the ultimate goal of the negotiation is to remove all sanctions immediately along with the closure of the Iranian nuclear file at the UN Security Council. Khamenei is staking his legitimacy within the conservative power circles in Tehran. His acquiescence implies that the Revolutionary Guards, whom the Supreme Leader commands, have also taken a leap of faith into the notion of normalized relations with the ‘Great Satan.’ A failure or reluctance to grant a prompt lifting of sanctions would break that delicate balance in the Iranian conservative camp, eviscerating the pragmatist Iranian president Rouhani’s ability to negotiate.

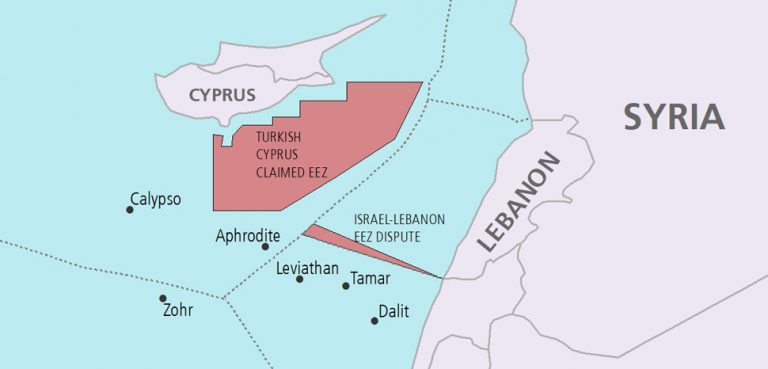

If a deal is reached, the Iranian riyal will bounce back and the Tehran stock exchange would rise in expectation of an invigorating flow of foreign investment. Iran’s price would be to dismantle hundreds of centrifuges while allowing more intrusive inspections of its nuclear research facilities. Ideally, diplomatic relations between Washington and Tehran would begin at a more formal level, allowing for a better coordinated and effective effort to confront regional crises from Syria to the Islamic State and Iraq. Should the deal fail, the currency could collapse while the hardliners in the Majlis would demand an intensification of enrichment activities, drowning out progressive voices including Rouhani’s. The US and Israel, in particular, would react; military options would replace diplomatic ones. Just as Israel’s airstrike against the Osirak nuclear reactor in Iraq in 1983 prompted then President Saddam Hussein to boost nuclear research, an Israeli or military strike against nuclear facilities in Iran could well set of a series of tit-for-tat steps, aimed at increasing tensions and a wider scale war. Such a war would possibly see the US and Israel become embroiled in a wider conflict involving Hezbollah in Lebanon, while talk of regime change in Damascus would intensify. Of course, oil prices would shoot back up to make oil and tar sands projects in North America profitable again.

This may explain why Canada’s Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who has openly backed the oil industry in Alberta, has adopted a very hostile attitude to Iran, terminating formal diplomatic ties in 2012. However, conservatives in North America should realize that many of their potential voters in the corporate world, including the oil services industry, would welcome an Iranian deal. Agreement this weekend would slam the market wide open for Western technology and oil companies to set up shop. Iran needs to upgrade its infrastructure and is in all but desperate need to build up its refining capacity – both for internal supply and to increase the value of its oil exports (just as Saudi Arabia does).

Iran has invited European companies, especially the big energy groups, to evaluate economic opportunities in Iran: “The Islamic Republic of Iran is ready to engage in constructive cooperation for the promotion of global energy security due to its vast resources of oil and gas,” so said President Rouhani after holding a meeting with Western private sector managers at Davos in 2014. That meeting was attended by Italy’s Eni, France’s Total, Britain’s BP, Russia’s Lukoil, GazpromNeft and several other companies. The meeting is also rumored to have attracted executives of US companies such as Exxon Mobil and/or Chevron. Rouhani has promised to pursue a foreign policy of “prudence and moderation” to restart the economy, adding that Tehran wants friendship and cooperation with “all countries that the Islamic Republic of Iran recognizes.” Rouhani did not mention Israel, but a successful outcome in terms of Syria (in Iran’s case success merely means Bashar al-Assad’s remaining in power) may also open up some channels to Israel.

The sanctions imposed on Tehran between the Islamic Revolution in 1979 and the identification of the nuclear enrichment program in 2003 have caused a loss in trade between Europe and Iran estimated in the hundreds of billions of dollars. The solution of the nuclear issue would have a considerable economic impact. European companies are monitored closely by the American authorities, fearful of running into financial penalties or exclusion from Western markets. Many seemingly out of touch ayatollahs and mullahs in Tehran have not forgotten what makes the world go round – they are not so blinded by the idealism and romantic attitudes that inspired such actions as the storming of the US embassy in Tehran and the related hostage crisis. Many of the students that took part in that episode regret the damage it has done Iran and now they are eager to fix the status quo by promoting the pragmatists. Hossein Mousavi, the leader of the banned Green Movement and former prime minister of the Islamic Republic is one such leader.

Europe is more than eager to get the sanctions lifted. The size of the trade between the EU countries and Iran in items that are allowed is a hint at what that trade could become when sanctions are lifted. In 2014, Germany’s exports to Iran grew by 30%, totaling 2.4 billion euros. France’s Renault and Peugeot, which have always held a very large share of the Iranian auto market throughout the Shah and Ayatollah years, has seen its exports hit by the latest sanctions. To circumvent the restrictions, Renault is said to be pondering a 45% purchase of the Iranian industrial group Pars Khodro.

President Barack Obama has a great opportunity to not only affect the future of relations between Washington and Tehran, but to alter the whole geopolitical framework of the Middle East. That is why Israel and Saudi Arabia are in fibrillation.

Both Rouhani and Obama are at a crossroads and both are having to gamble in a challenge unlike any other in the past few decades. The challenge is as much a part of the negotiation process itself as in dealing with the many domestic and regional obstacles. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delivered a dramatic speech to convince a Republican and almost treasonous Congress, considering the affront on President Obama’s authority, to prevent in any way an American understanding with the Iranians. In short, the head of a foreign government, just days ahead of an election at home – which he would win – has launched a new challenge to the American president on his home turf. Such an unprecedented event has proven to be very disruptive in relations between Washington and Tel Aviv. It may backfire on Netanyahu, who will now start his fourth term as prime minister with a decidedly unfriendly White House, which has nothing to lose. President Obama may well be tempted to secure an agreement with Iran even faster than before, conceding Iran what it wants most, which is an immediate halt to the sanctions.

Rouhani cannot sign anything without a clear commitment on this point. Such is the mandate he has from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, the regime hardliners, the Revolutionary Guards or Pasdaran, the conservative clergy but also, and more importantly, all moderate forces as well, especially those that led the ‘green’ revolt of 2009. Moderates and pragmatists agree on this point. The Iranian regime, while religious in inspiration, is also highly nationalistic, which is what has kept Iranians remarkably united in the face of severe hardships from war to embargo. No Iranian, whether he identifies with Khamenei or the greens or the left wing Tudeh, would accept a humiliating arrangement. For his part, President Obama has staked his political and historical legacy on a deal with Iran; it is too late for him to withdraw without losing face and credibility – which would be very damaging to the United States and its ability to influence international events far beyond the Middle East from Bogota to Beijing. Iran has much to lose as it is engaged addressing problems in Iraq and Syria, and in Iran itself it is balancing the internal economic situation with oil prices continuing to fall and world reserves increasing.

The Iranians know what they want: resume relations with the United States, secure business with Europe, and resume their role as major players in the Middle East, where, in a return to realpolitik after years of ideological politics, they now see themselves as a key ally in the war against the horrors of Islamic State.