On Sunday July 1, Mexican voters headed to the polling stations in the largest election in Mexican contemporary history: over 3,400 seats were up for grabs at local, state, and federal levels, including the presidency of the country and the whole Congress.

Yet this election should also be remembered for other equally pressing aspects. For one there was the backbiting from all political parties, and then there was the violence which saw 113 candidates from all political parties murdered prior to the Sunday elections. The latter is an unprecedented event and is yet unaddressed in the various political campaigns of every candidate.

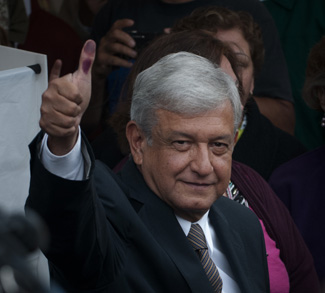

Around 62% of the electorate turned out to vote in the election. While still a decent figure, it shows that winners in recent elections have been unable to attract a significant number of the electorate in Mexico. The total of the nominal voter list for this 2018 election was 85, 953,712 million people; 63.45% of those turned out to cast their votes (54,537,000 million people approximately). The winner, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) obtained 52.96% of the votes, which means 28,359,567 million people cast their vote to elect the future president of the country – not even a third of the nominal list. This kind of result has prevailed in the last four presidential elections, and it’s a trend that should not be easily dismissed.

Last week’s result brought to the forefront of the political agenda the fact that Mexican voters are so fed up with the ruling class that they have decided to take a chance on the only option that was left trying. This, again, should not be taken lightly. The National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) and its candidate AMLO did not win supporters and votes because of his proposals for national policies. A large portion of the people that cast their vote for him did so as a punishment vote, out of sweeping, profound frustration over the last three administrations.

AMLO’s victory ushers a four-year-old party into the presidential seat, with little practical governing experience, and whose outsized leader has promised to radically and peacefully transform the country. Among his campaign promises are a strengthening of the rule of law and democracy; ruling with honesty and ending privileges and immunities; the decentralization of ministries; fixing the prices of agricultural products; dealing with the energy crisis; eliminating corruption; fighting job insecurity and poverty; increasing the state’s role in economic development; guaranteeing jobs and access to free education for youngsters, with a monthly stipend; providing paid apprenticeships to those currently not studying or working; increasing pensions for the elderly; guaranteeing 100% admission rates to university studies; and “living humbly.”

Though on paper these policies look certainly promising, AMLO has made seemingly contradictory statements throughout his political career and during his campaign. He has also steered clear of declaring a firm stance on many important matters, and avoided going into concrete details as to how he plans to achieve his campaign promises. While he has claimed to be in favor of radically transforming Mexico, his post-election speeches hint that he will hardly pursue a rapid and revolutionary upheaval to shock the system to the core. One of those contradictions is that whilst he has promised repeatedly that he will uproot corruption and live humbly, he has already sent signals that he refers only to everyone else; not himself or his inner circle. Already he is backed by the multimillionaire Alfonso Romo; he postulated former mining union leader Napoléon Gómez Urrutia, accused of stealing millions of pesos from workers, to the Senate; and various family members of the disgraced former Teacher’s Union leader Elba Esther Gordillo are among MORENA’s supporters.

While the election result is indeed a seismic change, it is still too early to brand it as the final step in the consolidation of Mexican democracy, and the end of party rule as we know it, or at least the end of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The same was argued after the elections of 2000 and 2006, and the party was able to canalize the errors of the then incumbent administration. Secondly, in terms of MORENA as a political organization, despite claiming it is not a political party, it resembles one in every way one, and in many respects emulates the practices of the former hegemonic PRI party. There’s one man at the top, AMLO, who prevails over dubious, non-transparent practices to select candidates to governmental positions. Thirdly, there is no real ideological party affiliation in Mexico. The majority of the Mexican electorate do not vote based on concrete political ideologies, as the election of AMLO shows. Rather, they voted for him because there was nobody else they considered to be a better choice. Lastly, the long-criticized clientelism, nepotism, and opacity that characterized PRI for 71 years are now present not only in all of the other political organizations, but in society as a whole. Many MORENA members were previously affiliated with other political parties and decided to get on the MORENA bandwagon in search of a governmental post they considered unattainable with their former political parties. The old authoritarian system has been preserved out of convenience and this is the main hurdle to overcome.

How will a Mexico under AMLO look like? That is one of the most pressing questions in the immediate aftermath of the election. There are still many open-ended questions as to which AMLO will govern: the pragmatist or the firebrand. It is still up in the air whether some of the inconsistencies, incongruences, flip-flops, ironies, choice of candidates, and lack of clarity regarding his policies were an electoral tactic or a worrisome trait. It will not be until he takes office that we will be able to grasp a more granular understanding of his ruling style.

AMLO will also have to rule a country mourning over 150,000 people murdered over the last 18 years and face a tightening grip of oil pipelines by criminal organizations as well as the uncontrolled spiral of violence in the country. His administration will coincide with increasingly fragile and deteriorating relations with the United States, and many of AMLO’s proposals to deal with security may be further tied up by Trump, especially if he is unable to curb insecurity in the short-term. The Mexican government still relies on the US intelligence data to catch criminals. Mexico’s next president needs to fully understand the motivations behind Trump’s view of Mexico. For him it is a personal issue imbued by a political electoral dynamic crucial to mobilizing his base. Arguing that the strategy should be to make Trump respect Mexico is not only a Panglossian attitude, but it is doomed to failure. Both leaders stand today at crossroads and they can either be partners in success or accomplices in failure.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.