In Yemen there is no longer a government or a president. On January 22, after the Houthi, (Zaydi Shiites) militiamen in the north besieged the presidential palace in Sana’a, both interim President (since 2012) Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi and Prime Minister Khaled Bahah (of a caretaker government which secured parliamentary confidence in December 2014), resigned. Washington has closed its embassy and many other countries, Western and non, have done likewise. Four southern governors, including those from Aden and Abyan, which has been the epicenter of the US drone campaign against al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), have refused to resign, in solidarity with President Hadi. Houthi militias dispersed an impromptu pro-government demonstration days after the takeover; the occasion served as an opportunity for the Houthis to wield some power as they brandished weapons in the streets and made numerous arrests.

The Houthi religious-political-military movement was born in the eighties in the northern region of Saada under the leadership of Husayn al-Huthi (deceased), expressing a Zaydi (a Shiite sect which ruled the Imamate in northern Yemen until 1962) pushback against Sunni dominance in the country, which is supported by the central government and by Saudi funds. After the resignation of President Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2011, the Houthis have managed to take over control of a vast area thanks, in no small part, to the retreat of army units still loyal to Saleh. In doing so they defeated the Sunni militias linked to the Islah Party (which includes the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists). Meanwhile, Ansarullah, the Houthi political movement, was taking part in the ‘national dialogue’ process to re-draft the Constitution; therefore, the Houthis have managed to gain both military and political ground, not unlike Hezbollah did in Lebanon during the 1990s.

Last August, the Houthi militias exploited the government’s reduction of fuel subsidies to occupy the capital Sana’a. At first, they did this ‘peacefully,’ but inevitably they clashed with security forces and pro-government militias. Finally, the Houthis, along with all other parties in the Yemeni quagmire, signed the National Peace Agreement (NPA) in September, which managed to reduce the urban violence for a while under the rule of a temporary government. The NPA established the formation of a caretaker government, which included the backing of Ansarullah and another separatist group from the South.

Yet the Houthis have rejected the attempt at federal reform, because under this plan their strongholds would be grouped into a new macro-region of Azal, which is densely populated, poor in energy resources, and landlocked.

The Houthis then retaliated by kidnapping Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak, Secretary of Reforms, and holding the presidential palace and the private residence of the president under siege, which culminated in an attack on the prime minister’s convoy.

A Web of Rivalries

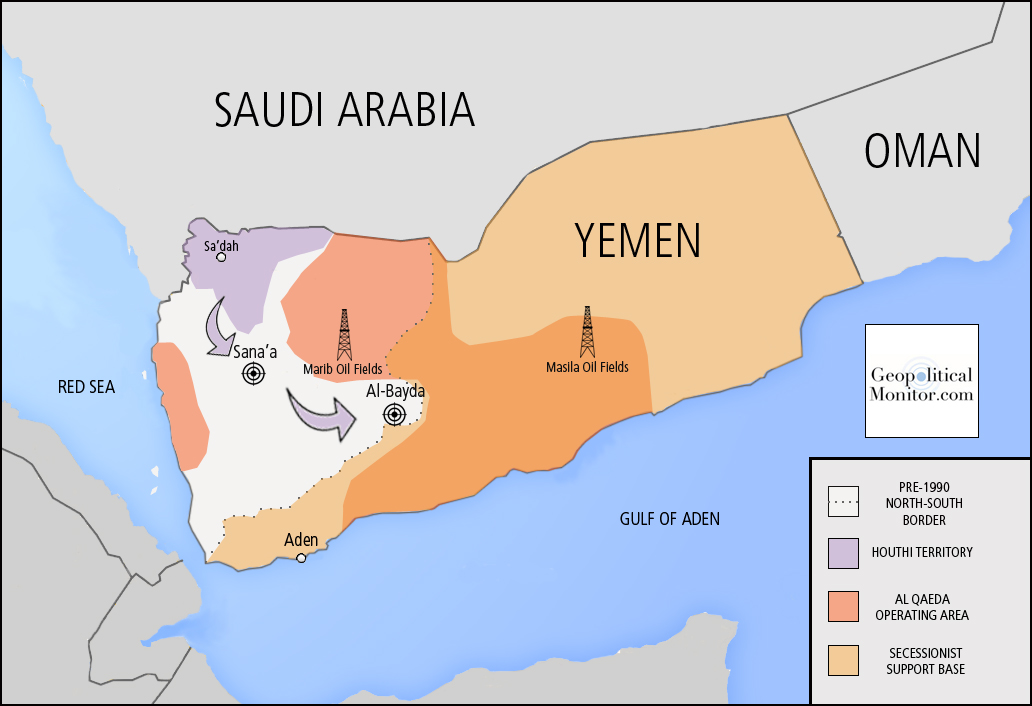

Were Yemen’s problems simply confined to Houthi/Sunni rivalries, a solution could be found. The problem is that Yemen has at least four separate conflicts within its borders. There is a clash between the northern insurgents and the central authority (mirrored in the south by the Southern Movement, which is clearly demanding independence). Then the Islah movement and the old regime’s elite, headed by Ahmed Saleh (son of the exiled former president Saleh), has been challenging the transitional authority. The Army has served as the ‘battleground’ for this conflict, where loyalties are not to the central government but to tribal leaders and their various allegiances. This phenomenon has effectively left the central government with no military forces through which to challenge the much more dedicated and disciplined factional militias, allowing the Houthis to gain territory very quickly. The fact that the Sunnis are divided among supporters of the former president and his clan and the transitional authority has created a vacuum making the Houthi advance even more dramatic. Ansarullah has, in fact, taken over territories in the western coastal region (including the Hodeida, oil terminal), as well as in the central Sunni strongholds of Marib or Ibb. The vacuum has also allowed al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) to regain some strength against a stripped central military force. AQAP has attacked police and military installations as well as Houthis (their main enemy). Amid the accentuated climate of tribal division, the Sunni tribes, whether against or in favor of former president Saleh, have tended to side more alongside AQAP than show even the least bit support for the Shiite Houthis.

There have been accusations that the Houthis have been receiving funding and weapons from Iran while Saudi Arabia, which had backed Saleh at first and then the transitional government, has suspended financial aid to Yemen. The problem for Washington is that the Houthis represent the best way to contain AQAP in Yemen, given the collapse of the temporary government and the official armed forces. However, the Houthis are not especially sympathetic to the United States, given the latter’s support for Saudi Arabia – which has engaged in frequent skirmishes against the Houthis over the past few years and even before President Saleh’s resignation. President Obama will surely discuss the Yemen situation with the new Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz in order to relaunch regional cooperation; nonetheless, continued talks between the United States and Iran over containment of the latter’s nuclear program should also leave some room for the Houthis to take up their struggle against AQAP.

Any issue of US military involvement to try and restore order is very delicate because Yemenis, according to polls, have shown some of the highest rates of ‘anti-Americanism’ in the Arab world. Such interventions, or even the perception of US support for the temporary government, would only add to the divisions. Foreign intervention could prompt some people to support the militants against the ’invader,’ which would then truly risk creating another Afghanistan, albeit one much closer to the world’s largest oil producer.

Yemen is the poorest country in the Arab world; it has some oil, but reserves are dwindling and there is no investment in new exploration because of high security risks. Recent governments – especially the one led by Saleh – have not had any economic plan to deal with the ‘post-oil’ future. Saudi Arabia is understandably concerned, as it is clear that Yemen has descended into a situation of chronic instability and militancy.

Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil producer, fears this instability and the void that has enabled insurgent groups such as AQAP to establish territorial footholds. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Emirates are concerned by the prospect of Yemen becoming another Afghanistan, which has had a destabilizing effect on neighboring Pakistan. Much like Afghanistan, and adding to security concerns, Yemen is poor; the population faces a number of health and economic difficulties such that the Yemeni government is always on the brink of having to confront a disaster. Yemen could yet become another failed state overrun by extremists in an area already marked by the presence of that better-known failed state of Somalia. Through the Bab-al-Mandab, Yemen occupies a strategic position at the entry of the Red Sea, which is one of the world’s leading cargo shipping routes; it is also the main route for the shipment of oil from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States. Any unrest in Yemen is a cause of concern in Riyadh, the other capitals of the Gulf, and inevitably in the West as well.

Saudi Arabia is not only concerned by the growing risk of terrorism from Yemen, it is also worried by the spillover effects of the Shiite, specifically the Zaidi Shiite, rebellion in northern Yemen. After suffering intense bombardment last December, the Zaidi rebels have tried to come to an agreement with the Saudi-backed Yemeni government. Meanwhile, having incurred heavy bombardments for the past few years, the government of Yemen has denied the Zaidi rebels request for an unconditional ceasefire. The government is concerned that the Zaidis have not made an explicit reference to refusing to attack Saudi Arabia, which is also home to a Zaidi Shiite community in the areas bordering Yemen. Saudi Arabia became very involved in suppressing the Houthi revolt in 2010, though the Zaidi rebellion began in 2004 and has so far left thousands dead and driven 200,000 people from their homes. Ironically, one of the Yemeni social phenomena that is raising concerns in Saudi Arabia is the spread of Wahhabi or Salafist interpretations of Islam among Yemeni youth – from Saudi Arabia.

While the United States has already given Yemen at least USD 100 million in military aid, it would be wiser to target Yemen’s socioeconomic problems. Oil production is expected to end by 2017, while Yemen’s population – already experiencing a 40% unemployment rate – may double by 2035 at current birth rates. While all Arab countries are characterized by large percentages of youth, Yemen is the country where this phenomenon is highest, seeing as 45% of the population is below 15 years of age. Considering the stunted opportunities for economic growth, an imminent oil shortage, and the severe water problems, Yemen is a social and security time bomb.