In 1991, Abiy Ahmed was 14 years old when he decided to take up arms against the Ethiopian state. At that time, the country had endured nearly 17 years of repressive rule by a Marxist regime noted for its questionable detentions, extrajudicial killings, and abysmal governance. Having witnessed the incarceration of his father and the slaying of his older brother, Ahmed’s decision to join the uprising served as one of the limited means through which Ethiopian citizens could communicate grievances. The successful overthrow of the Workers’ Party of Ethiopia ushered in the emergence of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of ethnically aligned parties that has governed Ethiopia ever since.

Fast-forward nearly 30 years later and Abiy Ahmed, who is now nearing his 2nd year in office as prime minister, may be confronting a new insurrection that has already exposed weakness in the delicate, post-civil war traditions of power-sharing among Ethiopia’s major ethnic groups.

Having averted an attempted coup and an assassination plot, Abiy Ahmed’s most pressing challenge now involves securing victory in elections scheduled for August. For the first time since the collapse of the Marxist government, the EPRDF will not be contesting elections as a coalition. The dissolution came about following a decision by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) to opt-out of Ahmed’s recently launched Prosperity Party, which seeks to solidify closer ties between the remaining EPRDF coalition members by merging them into a single political entity, as opposed to the traditional partition of parties based on ethnic lines. The move underscores a critical component of Ahmed’s reform agenda, which is centered upon an agnostic form of Ethiopian nationalism rooted in allegiance to the country as opposed to ethnolinguistic groups.

For its part, the TPLF remains in search of partners who support preservation of Ethiopia’s ethnic federalist system, which is mandated in the country’s constitution. Regional autonomy remains a sticking point in the country’s political debates today, and results from the 2020 election could provide a pulse as to the country’s willingness to either preserve, or amend, the ethnic federalist system. Nevertheless, aggressive challenges to the status quo would likely precipitate worsened relations and open conflict between Ahmed and regional leaders, creating a heightened risk of potential balkanization of the country.

In addition to political opposition, Ahmed’s government is also confronting a growing insurgency movement in Western Oromia, as armed factions have split from political parties to engage in separatist activities. Reports of a brutal crackdown by Ethiopian security forces harks back to the measures affiliated with the Derg era, as the military junta was once known. The situation in the Oromia region has been dire enough to compel authorities to shut off telecommunication services. Should insecurity persist, the elections may exclude the Oromia region altogether, a move that could potentially turn even the region’s moderate residents against the state.

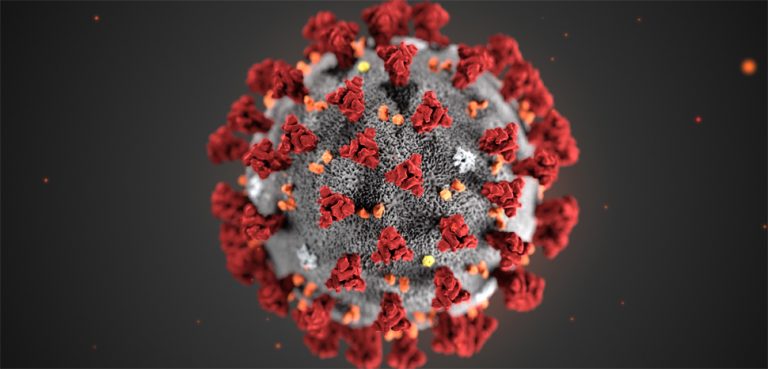

While the Prosperity Party will certainly benefit from its comprised coverage of strong parties representing the Oromia, Amhara, and Southern regions, it is still far from guaranteed a victory ahead of the August elections. Given the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19 and its potential impact in Ethiopia, a preliminary assessment by the government is already underway to determine the feasibility of holding elections in August. A delay could complicate questions surrounding legitimacy, a scenario that most opposition parties, including the TPLF, are fervently attempting to avoid.

The potential fallout from COVID-19 could prove to be especially damaging for Ethiopia, as the government’s performance will likely play a decisive role ahead of the 2020 elections. The country’s most prized and profitable state-owned entity, Ethiopian Airlines, is reeling from cancellations and suspension of flights that could amount to losses of more than $190 million USD, draining valuable revenue from the government’s stretched coffers.

Furthermore, the country remains host to a number of refugee camps, and backlash against migrants and foreigners has already been documented. Fears of overload for Ethiopia’s woeful healthcare system, particularly in rural communities, may feed into support for the opposition, which will be angling for strong ethnic alignment to preserve Ethiopia’s federalist system. While the country remains early in its prevention efforts, the government has already instituted closures of schools and barred public gatherings. Low-level prisoners have also been released as a means to contain the spread of the virus.

Having earned plaudits early on in his administration for his desire to bring about rapid change both within Ethiopia and across the African continent, challenges to Ahmed’s rule will not be easily extinguished. In spite of international accolades, widespread support from Ethiopian diasporas, and warming relations with the West, Abiy Ahmed and the Prosperity Party is fighting a war on multiple fronts, through both armed and political means. Withstanding the pressure will necessitate concessions that will undoubtedly slow the party’s reform agenda. Yet, if recent history is to be a guide, breakneck speed and idealism never did fare well in Ethiopia’s past. For a country not too far removed from the remnants of its last civil war, the risk of repeating history could lead to irreparable consequences.